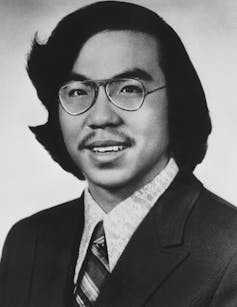

The legacy of Vincent Chin has recently been commemorated in a street sign bearing his name on the corner of Cass Avenue and Peterboro Street in Detroit’s historic Chinatown.

I was glad to see it. Watching the 1987 documentary “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” and learning about his life and Asian American activism changed my life.

I was 18 and taking my first Asian American studies class at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The film made me realize two things: Asian Americans are targets of racial violence, and Asian Americans across the ethnic spectrum could join together to fight for civil rights. This led to my passion for social justice.

I’m proud to now be a professor of Asian American studies and critical race theory who teaches my students about Vincent Chin.

So who was Chin, and why did his death catalyze an Asian American civil rights movement?

A fatal brawl

Chin, an Oak Park resident, was 27 years old on the night of his bachelor party, June 19, 1982. He got into a fight with two white men – Ronald Ebens, a Chrysler car plant supervisor, and Michael Nitz, an unemployed autoworker and Ebens’ stepson.

According to Racine Colwell, a dancer at the Fancy Pants Club in the Detroit area, Ebens shouted, “It’s because of you little motherf–kers that we’re out of work.” Detroit in the early 1980s was in an automotive slump. People blamed Japanese auto imports and the Japanese people, in general, for the economic downturn. The assailants didn’t seem to understand or care that Chin was actually Chinese.

After the fight between Chin and Nitz and Ebens, Chin and his friends ran out of the club. Ebens and Nitz ran after them, with Nitz grabbing a baseball bat from his car. When they found Chin outside a McDonald’s on Woodward Avenue, Nitz held Chin while Ebens beat his body and head with the bat. They were stopped by two off-duty police officers who had been inside the fast-food restaurant.

After the attack, Jimmy Choi, a member of the bachelor party, cradled Chin in his arms. He said that Chin’s last words were “It’s not fair.” Chin died four days later.

Ebens and Nitz were charged with second-degree murder, but their lawyers pleaded the charge down to manslaughter. At the end of the trial, Judge Charles Kaufman fined them US$3,000 each and sentenced each to three years’ probation, explaining: “These weren’t the kind of people you send to prison. … You don’t make the punishment fit the crime. You make the punishment fit the criminal.”

Asian Americans organize for legal justice

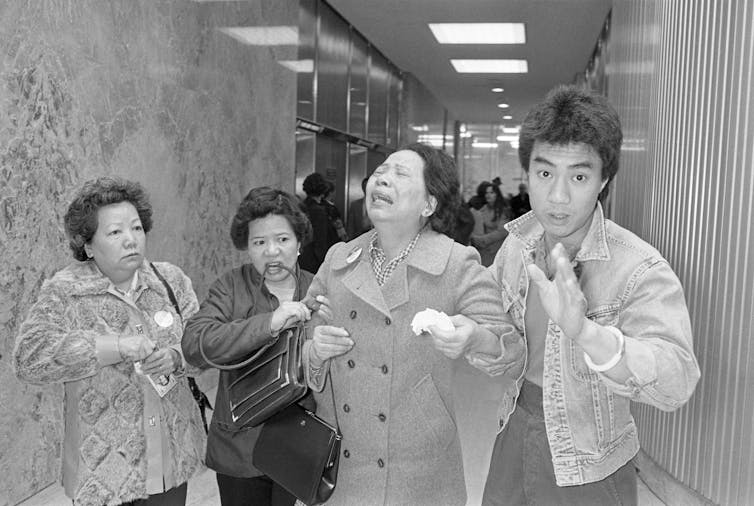

The sentencing enraged Chin’s friends, family and the greater Chinese and Asian American community of Detroit.

Activists of various Asian ethnicities and their non-Asian allies created American Citizens for Justice, an organization that pressured the Justice Department to investigate the violation of Chin’s civil rights and to see Ebens and Nitz imprisoned for Chin’s murder. Lily Chin, Vincent’s mother, was a key advocate in the pursuit of justice for her son, showing up to rallies and interviews to remind people of Vincent’s death for nearly a decade.

While there were other moments, such as the anti-eviction fight for the I-Hotel in San Francisco, that brought Asian Americans of all ethnicities together to fight for civil rights, Chin’s murder sparked a broad awareness. Asian Americans realized that what happened to Chin could happen to them.

American Citizens for Justice held press conferences and gained support from local African American activists in Michigan and national Black leaders like Jesse Jackson, whose presence helped bring more attention to the Chin tragedy.

Activists were successful in forcing the FBI to open an investigation. The resulting 1984 federal trial was the first time the Justice Department had argued that the civil rights of an Asian American person had been violated. Nitz was found not guilty on two counts. Ebens was found guilty and sentenced to 25 years in prison. However, a 1986 federal appeals court ruling overturned the conviction, freeing Ebens.

A civil suit filed against Ebens and Nitz on behalf of Lily Chin was settled out of court in 1987. Nitz agreed to pay $50,000 and Ebens $1.5 million – the projected income that Chin would have made had he lived.

Nitz fulfilled his debt, but Ebens made only a few payments. By 1987, Ebens had been unemployed for five years. He stopped making payments after he moved to Nevada. Estimates in 2016 place Ebens’ debt to the Chin estate at over $8 million, including accumulated interest.

Chin’s death had a profound impact on the criminal justice system in Michigan and nationally. Michigan made it harder to plead down murder charges to manslaughter and required prosecutors to be present at sentencings to face victims. Nationally, victim impact statements are now commonplace. Victims and their families now have more of a voice in the justice system.

Chin’s death spurred Pan-Asian American activism across the U.S., leading to the eventual founding of organizations like Asian Americans Advancing Justice in 1991 and Stop Asian American Pacific Islander Hate in 2020. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Stop AAPI Hate recorded violence against Asians happening in the U.S. and educated people about anti-Asian racism.

Today, Asian Americans fight for social justice through organizations like these and 18 Million Rising, a group that advocates for racial justice for Asian Americans and all marginalized people.

This is the lasting legacy of Vincent Chin.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  3 weeks ago

3 weeks ago

Comments