He has been called the Nostradamus of US presidential elections. Allan Lichtman has correctly predicted the result of nine of the past 10 (and even the one that got away, in 2000, he insists was stolen from Al Gore). But now he is gearing up for perhaps his greatest challenge: Joe Biden v Donald Trump II.

Lichtman is a man of parts. The history professor has been teaching at American University in Washington for half a century. He is a former North American 3,000m steeplechase champion and, at 77 – the same age as Trump – aiming to compete in the next Senior Olympics. In 1981 he appeared on the TV quizshow Tic-Tac-Dough and won $110,000 in cash and prizes.

That same year he developed his now famous 13 keys to the White House, a method for predicting presidential election results that every four years tantalises the media, intrigues political operatives and provokes sniping from pollsters. Long before talk of the Steele dossier or Mueller investigation, it all began with a Russian reaching out across the cold war divide.

“I’d love to tell you I developed my system by ruining my eyes in the archives, by deep contemplation, but if I were to say that, to quote the late great Richard Nixon, that would be wrong,” Lichtman recalls from a book-crowded office on the AU campus. “Like so many discoveries, it was kind of serendipitous.”

Lichtman was a visiting scholar at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena when he met the world’s leading authority in earthquake prediction, Vladimir Keilis-Borok, who had been part of a Soviet delegation that negotiated the limited nuclear test ban treaty with President John F Kennedy in Washington in 1963.

Keilis-Borok had fallen in love with American politics and began a collaboration with Lichtman to reconceptualise elections in earthquake terms. That is, as a question of stability (the party holding the White House keeps it) versus earthquake (the party holding the White House gets thrown out).

They looked at every presidential election since Abraham Lincoln’s victory in 1860, combining Keilis-Borok’s method recognising patterns associated with stability and earthquakes with Lichtman’s theory that elections are basically votes up or down on the strength and performance of the party that holds the White House.

They came up with 13 true/false questions and a decision rule: if six or more keys went against the White House party, it would lose. If fewer than six went against it, it would win. These are the 13 keys, as summarised by AU’s website:

1. Party mandate: After the midterm elections, the incumbent party holds more seats in the US House of Representatives than after the previous midterm elections.

2. Contest: There is no serious contest for the incumbent party nomination.

3. Incumbency: The incumbent party candidate is the sitting president.

4. Third party: There is no significant third party or independent campaign.

5. Short-term economy: The economy is not in recession during the election campaign.

6. Long-term economy: Real per capita economic growth during the term equals or exceeds mean growth during the previous two terms.

7. Policy change: The incumbent administration effects major changes in national policy.

8. Social unrest: There is no sustained social unrest during the term.

9. Scandal: The incumbent administration is untainted by major scandal.

10. Foreign/military failure: The incumbent administration suffers no major failure in foreign or military affairs.

11. Foreign/military success: The incumbent administration achieves a major success in foreign or military affairs.

12. Incumbent charisma: The incumbent party candidate is charismatic or a national hero.

13. Challenger charisma: The challenging party candidate is not charismatic or a national hero.

Lichtman and Keilis-Borok published a paper in an academic journal, which was spotted by an Associated Press science reporter, leading to a Washington Post article headlined: “Odd couple discovers keys to the White House.” Then, in the Washingtonian magazine in April 1982, Lichtman used the keys to accurately predict that, despite economic recession, low approval ratings and relative old age, Ronald Reagan would win re-election two years later.

That led to an invitation to the White House from the presidential aide Lee Atwater, where Lichtman met numerous officials including then vice-president George HW Bush. Atwater asked him what would happen if Reagan did not run for re-election. Lichtman reckoned that a few important keys would be lost, including incumbent charisma.

“Without the Gipper, forget it,” Lichtman says. “George Bush is about as charismatic as a New Jersey shopping centre on a Sunday morning. Atwater looks me in the eye, breathes a huge sigh of relief, and says, thank you, Professor Lichtman. And the rest is history.”

For the next election, Bush was trailing his Democratic challenger Michael Dukakis by 18 percentage points in the opinion polls in May 1988, yet Lichtman correctly predicted a Bush victory because he was running on the Reagan inheritance of peace, prosperity, domestic tranquillity and breakthroughs with the Soviet Union.

That year Lichtman published a book, The Thirteen Keys to the Presidency. But he was still derided by the punditry establishment. “When I first developed my system and made my predictions, the professional forecasters blasted me because I had committed the ultimate sin of prediction, the sin of subjectivity.

“Some of my keys were not just cut and dried and I kept telling them, it’s not subjectivity, it’s judgment. We’re dealing with human systems and historians make judgments all the time, and they’re not random judgments. I define each key very carefully in my book and I have a record.”

He adds: “It took 15 to 20 years and the professional forecasting community totally turned around. They realised their big mathematical models didn’t work and the best models combined judgment with more cut-and-dried indicators. And suddenly the keys were the hottest thing in forecasting.”

Lichtman was a man in demand. He spoke at forecasting conferences, wrote for academic journals and even gave a talk to the CIA about how to apply the 13 keys to foreign elections. And his crystal ball kept working.

He predicted that George HW Bush would be a one-term president, even though he was riding high in polls after the Gulf war, causing many leading Democrats to pass on mounting a challenge. Then a call from Little Rock, Arkansas. It was Kay Goss, special assistant to Governor Bill Clinton.

“Are you really saying that George Bush can be beaten in 1992?” she asked. Lichtman confirmed that he was saying that. Clinton went on to win the Democratic primary election and beat Bush for the White House. “The Clintons have been big fans of the keys ever since,” Lichtman notes.

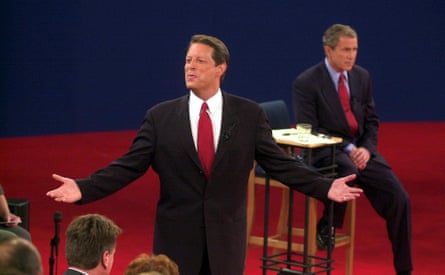

The one apparent blot on Lichtman’s copybook is the 2000 election, where he predicted victory for the Democratic vice-president Al Gore over George W Bush, the Republican governor of Texas. Gore did win the national popular vote but lost the electoral college by a gossamer-thin margin. Lichtman, however, believes he was right.

“It was a stolen election. Based on the actual votes, Al Gore should have won going away, except for the discarding of ballots cast by Black voters who were 95% for Gore. I proved this in my report to the United States Commission on Civil Rights. One out of every nine to 10 ballots cast by a Black voter was thrown out, as opposed to one out of 50 cast by a white voter.

“Most of those were not so-called hanging chads. They were over-votes because Black people were told punch in Gore and then write in Gore, just to be sure, and those ballots were all discarded. Political scientists have since looked at the election and proved I was right. Al Gore, based on the intent of the voters, should have won by tens of thousands of votes.”

He adds: “I contend I was right about 2000 or at a minimum there was no right prediction. You could argue either way. I contend – and a lot of people agree with me – that I’m 10 out of 10. But even if you say I’m nine out of 10, that’s not bad.”

Perhaps Lichtman’s most striking prophecy, defying polls, commentators and groupthink, was that Trump – a former reality TV star with no prior political or military experience – would pull off a wildly improbable win over the former secretary of state and first lady Hillary Clinton in 2016. How did he know?

“The critical sixth key was the contest key: Bernie Sanders’s contest against Clinton. It was an open seat so you lost the incumbency key. The Democrats had done poorly in 2014 so you lost that key. There was no big domestic accomplishment following the Affordable Care Act in the previous term, and no big foreign policy splashy success following the killing of Bin Laden in the first term, so there were just enough keys. It was not an easy call.”

After the election, Lichtman received a copy of the Washington Post interview in which he made the prediction. On it was written in a Sharpie pen: “Congrats, professor. Good call. Donald J Trump.” But in the same call, Lichtman had also prophesied – again accurately – that Trump would one day be impeached.

He was right about 2020, too, as Trump struggled to handle the coronavirus pandemic. “The pandemic is what did him in. He congratulated me for predicting him but he didn’t understand the keys. The message of the keys is it’s governance not campaigning that counts and instead of dealing substantively with the pandemic, as we know, he thought he could talk his way out of it and that sank him.”

In 2020 Lichtman gave a presentation to the American Political Science Association about the keys as one of three classic models of prediction. In recent months he has delivered keynote addresses at Asian and Brazilian financial conferences, the Oxford Union and JP Morgan. As another election looms, he is not impressed by polls that show Trump leading Biden, prompting a fatalistic mood to take hold in Washington DC and foreign capitals.

“They’re mesmerised by the wrong things, which is the polls. First of all, polls six, seven months before an election have zero predictive value. They would have predicted President Michael Dukakis. They would have predicted President Jimmy Carter would have defeated Ronald Reagan, who won in a landslide; Carter was way ahead in some of the early polls.

“Not only are polls a snapshot but they are not predictors. They don’t predict anything and there’s no such thing as, ‘if the election were held today’. That’s a meaningless statement.”

He is likely to make his pronouncement on the 2024 presidential election in early August. He notes that Biden already has the incumbency key in his favour and, having crushed token challengers in the Democratic primary, has the contest key too. “That’s two keys off the top. That means six more keys would have to fall to predict his defeat. A lot would have to go wrong for Biden to lose.”

Lichtman gives no weight to running mate picks and has never changed his forecast in the wake of a so-called “October surprise” But no predictive model is entirely immune to a black swan event.

Speaking in the week that saw a jury seated for Trump’s criminal trial in New York involving a hush-money payment to a pornographic film performer, Lichtman acknowledges: “Keys are based on history. They’re very robust because they go all the way back retrospectively to 1860 and prospectively to 1984, so they cover enormous changes in our economy, our society, our demography, our politics.

“But it’s always possible there could be a cataclysmic enough event outside the scope of the keys that could affect the election and here we do have, for the first time, not just a former president but a major party candidate sitting in a trial and who knows if he’s convicted – and there’s a good chance he will be – how that might scramble things.”

Millions of people will be on edge on the night of 5 November. After 40 years of doing this, Lichtman will have one more reason to be anxious. “It’s nerve-racking because there are a lot of people who’d love to see me fail.” And if he does? “I’m human,” he admits. “It doesn’t mean my system’s wrong. Nothing is perfect in the human world.”

Biden v Trump: What’s in store for the US and the world?

On Thursday 2 May, 3-4.15pm ET, join Tania Branigan, David Smith, Mehdi Hasan and Tara Setmayer for the inside track on the people, the ideas and the events that might shape the US election campaign. Book tickets here or at theguardian.live

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  1 week ago

1 week ago

Comments