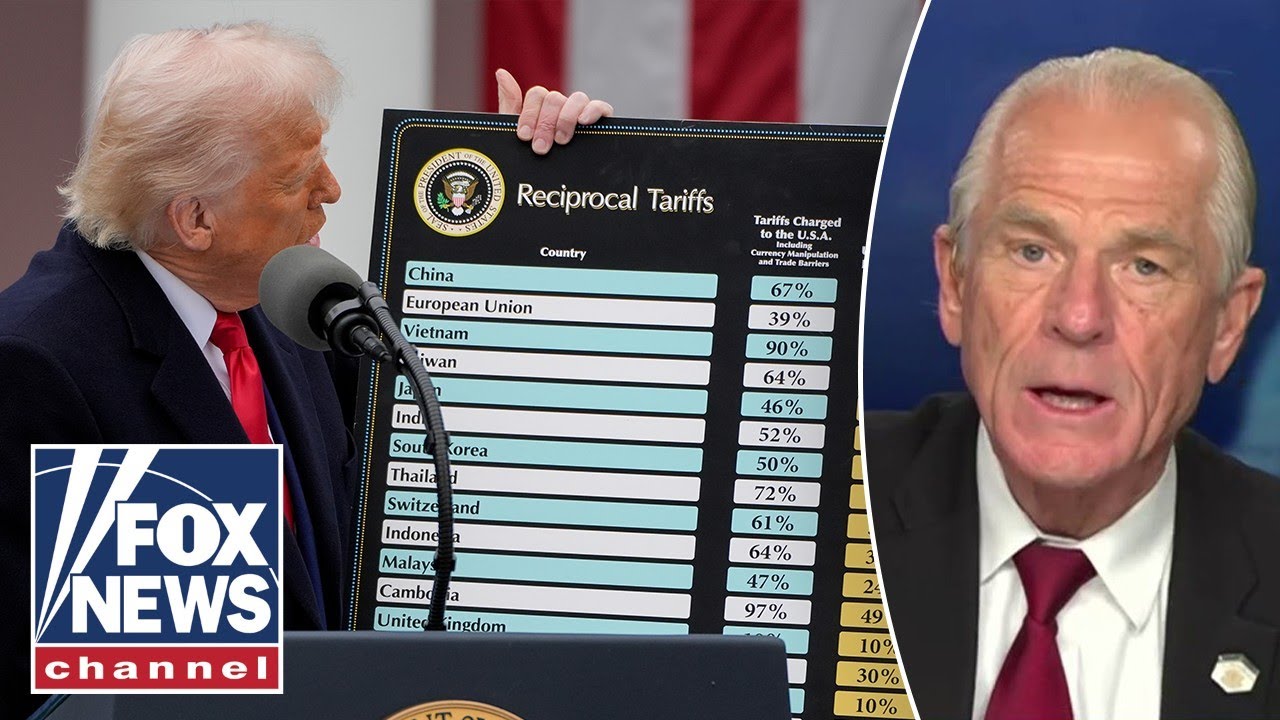

Donald Trump has repeatedly raised the specter of annexing Canada since his inauguration to a second term as president.

The president’s rhetoric about making Canada “the 51st state” may seem to project confidence, a 21st-century vision of manifest destiny, a belief in the United States’ right and obligation to expand.

Trump is not the first American leader to dream of northern expansion. To me, a historian of early U.S.-Canadian relations, these designs suggest not power, but weakness and simmering divisions inside the United States.

Early Americans’ lust for Canada

Even before independence, social conflict helped turn American eyes northward. Throughout the 18th century, England’s Colonial population in North America doubled every 25 years. Successive generations of Colonists along the Eastern Seaboard had to compete with each other, and with Indigenous people, for resources, arable land and trade.

These unhappy, land-hungry Colonists clamored for expansion, instigating a series of wars against both the French and Spanish empires for control of the northeastern half of the continent, culminating in the French and Indian War, from 1754 to 1763.

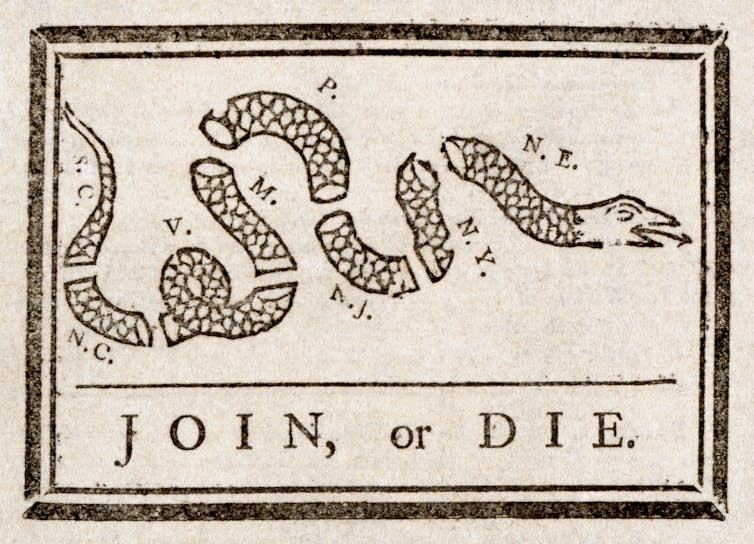

While these Colonists were animated by their thirst for expansion, they had little else unifying them. Many Americans today are familiar with the “Join, or Die” cartoon Ben Franklin printed, featuring a segmented snake with each section representing one of the Colonies. However, few realize that it was not crafted during the Revolution to unite Colonists against Britain, but in 1754, to rally divided British Colonists in their war against France.

Britain finished conquering Canada in 1763, but the empire never fully supported Colonial expansion northward. In the 1750s and 1760s, British troops forcibly removed French colonists from Acadia in Nova Scotia and recruited thousands of Colonists from neighboring New England to move north. These settlers had long imagined the region rich in fishing and timber to be a land of opportunity. But disillusioned by the financial cost of sustaining their settlements, many of these Colonists returned to New England by the early 1770s.

Attempts to settle other lands ceded by France were no more successful. Fearful that Colonists might provoke a costly war with Indigenous people, Parliament issued the Proclamation of 1763, which attempted to protect native land by discouraging Colonial expansion westward. Many Colonists turned against Britain in response, especially those like George Washington, who had speculated in the land west of the Appalachian Mountains.

The failed invasion of Canada

In the earliest months of the Revolution, the Continental Congress authorized an American invasion of British-occupied Quebec. In a letter addressed to “Friends and Brethren” of Canada, Washington himself implored Canadians to join invading troops. “The Cause of America, and of Liberty, is the Cause of every virtuous American Citizen,” he wrote. “Come then, ye generous Citizens, range yourselves under the Standard of general Liberty.”

But at home, Colonists were far from united in their rebellion. Historians estimate that around 20% of the white Colonial population, more than 500,000 people, remained loyal to Britain, and an even larger number hoped to remain neutral.

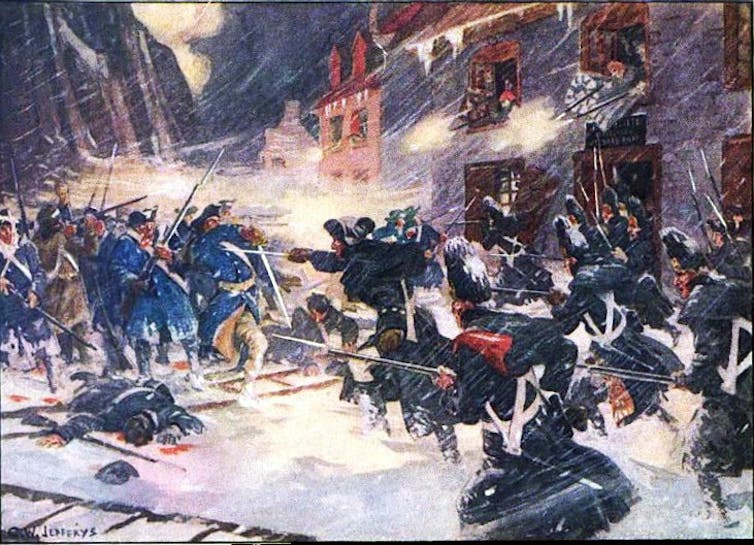

The difficult realities of conquest also turned many soldiers against the invasion of Canada. In late October 1775, nearly a quarter of the underfed and overworked troops under the command of soon-to-be turncoat Benedict Arnold abandoned their arduous journey through interior Maine toward Canada. The soldiers who carried on prayed these deserters “might die by the way, or meet with some disaster, Equal to the Cowardly dastardly and unfriendly Spirit they discover’d in returning Back without orders.”

The more resilient troops who reached Quebec were emphatically defeated by British forces in December, making Washington skeptical of any future efforts to attack Canada.

19th-century divisions

Following American independence, tens of thousands of loyal Colonists sailed north to Canada, determined to build British colonies that would become what one of these refugees called “the envy of the American States.” Their presence on the contested northern border was an unsettling reminder to the new American nation about the power Britain still exerted on the continent.

Conflict with Britain over land and trade in the early 1800s reopened old divisions among Americans. Virginia Congressman John Randolph expressed his frustrations with renewed calls for a northern invasion. “We have but one word, like the whip-poor-will, but one eternal monstrous tone,” an exasperated Randolph noted, “Canada! Canada! Canada!”

The debate over Canada was one of many issues dividing the nation, and as President James Madison would later explain, he hoped that war would help unify a polarized nation. His gamble paid off, but only after opponents from New England flirted with the idea of secession to negotiate their own end to conflict.

When the popular editor and columnist John O’Sullivan called for the annexation of Texas and war with Mexico in 1845, he also suggested the annexation of Canada would naturally follow. The anti-expansionist response united pacifists, abolitionists and a variety of religious and literary figures, helping deepen the divides that would lead to the Civil War.

Annexation talk in the 20th century

Trump’s posturing has served to unite Canadians and revive Canadian nationalism. In the U.S., most people seem to understand the practical hurdles of adding a new state or dismiss the idea altogether.

One example of annexation talk from the 20th century, however, might serve as a warning to Trump, showing how aggressive rhetoric toward Canada has led to political defeat. In 1911, a bill creating free trade with Canada passed Congress with the support of President William Taft, despite objections from protectionists in both parties.

In an attempt to have the agreement defeated in the Canadian Parliament, U.S. opponents from both sides of the aisle attempted to stir popular sentiment against the U.S. in Canada. Champ Clark, the Democratic speaker of the House and a front-runner for the presidential nomination in 1912, seized on the moment.

“I hope to see the day when the American flag will float over every square foot of the British North American possessions, clear to the North Pole,” Champ proclaimed on the House floor. William Stiles Bennet, a Republican, proposed a resolution that would authorize the president to begin negotiations for annexation.

Their approach to defeating the trade agreement worked, at least in Canada. In the general election of September 1911, worried Canadian voters ousted the Liberal Party, which had supported free trade, and the new Conservative majority rejected the agreement.

Back home, however, the plan backfired. Woodrow Wilson, not Clark, secured the Democratic nomination in 1912 and would go on to defeat both the incumbent Taft and former President Theodore Roosevelt. The bluster led not to success and victory, but loss and defeat.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  1 month ago

1 month ago

Comments