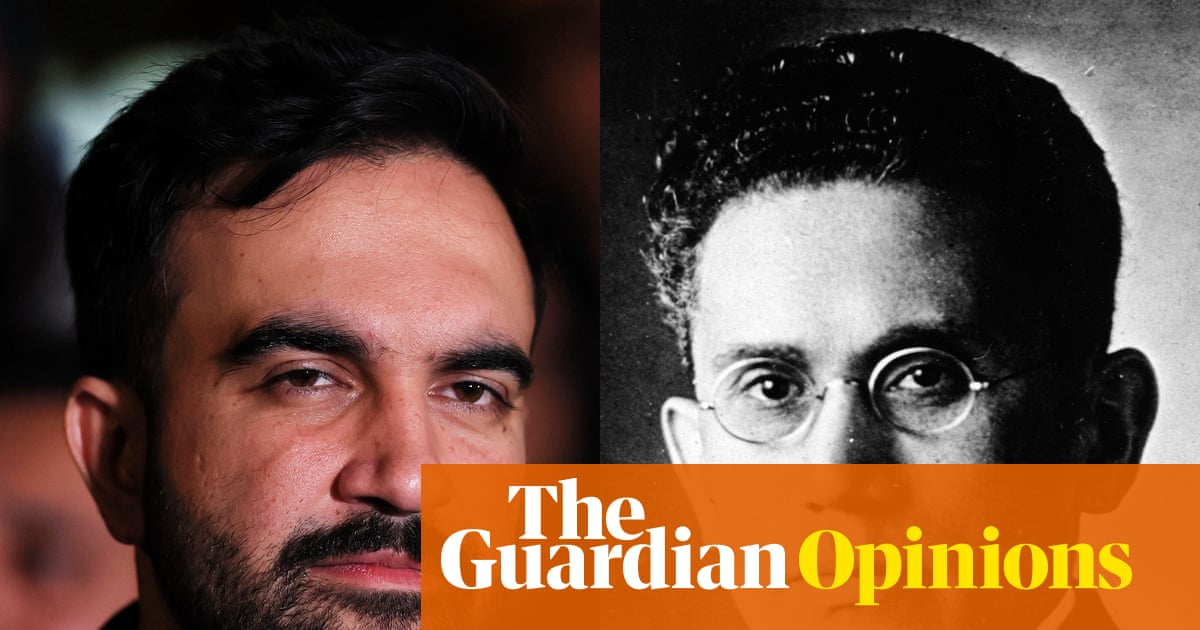

Twenty-two years ago, a dark-haired, bespectacled young man vanished off the streets of San Francisco. Daniel Andreas San Diego, a 25-year-old information technology specialist, diehard vegan and animal rights activist, was the FBI’s main suspect in a series of pipe bombings that exploded in front of the headquarters of Chiron Corporation and Shaklee Corporation, two Bay Area companies, in August and September of 2003.

Communiques attributed to the Revolutionary Cells – Animal Liberation Brigade were posted to the website of an animal rights magazine, claiming the attacks were carried out to highlight both firms’ alleged work with Huntingdon Life Sciences, a British research company that conducted tests for pharmaceutical, biotechnology and other chemical companies and had drawn the ire of activists on both sides of the Atlantic opposing its tests on animals.

In early September of this year, San Diego stood in a plexiglass dock at Westminster magistrate’s court in London, wearing a white button-down shirt and slacks, and guarded by several correctional officers. Now 47 years old, his hair is graying and his face has more wrinkles than the mugshots of a beaming, earringed young man the FBI disseminated during their 21-year search for him.

San Diego is fighting extradition to the United States on federal charges for the three political bombings, which injured no one. If extradited and convicted in the US, he could face 90 years behind bars, a potential life sentence. Armed with some of the UK’s most formidable human rights barristers, he has turned his extradition fight into a courtroom referendum on the compromised state of American justice under Donald Trump. Per his case docket in the northern district of California, San Diego does not have an attorney of record and has not entered a plea in his case.

The case also sheds a new light on an almost-forgotten chapter in American extremism - the post-9/11 “green scare”, when a growing federal law enforcement apparatus claimed “the No 1 domestic terrorism threat is the ecoterrorism, animal-rights movement”, as the FBI deputy director for counter-terrorism John Lewis stated in 2005 Senate testimony. Dozens of militants involved in torching development projects in the wilderness, freeing animals in testing facilities and leading mainstream campaigns against companies involved in such practices were prosecuted and convicted in a massive crackdown on the social movement. Until his capture, San Diego was one of the last fugitives from this era.

But it’s an important one in understanding federal law enforcement policies today, multiple experts say. The crackdown institutionalized law enforcement’s focus on social movements and activism, said Will Potter, a journalist and author of the 2011 book Green Is the New Red, at the price of the violent far-right militancy responsible for the majority of domestic terrorism incidents in the past decade.

“People don’t know this history, and now we’re seeing attacks on social movements and anti-fascists ramping up quickly,” said Potter. “Now, the government’s powers of going after social movements as terrorists have been inherited by an authoritarian, and measures that were considered radical after 9/11 are now viewed as normal.”

“The era in which this case arose almost seems quaint, looking back,” said Ben Rosenfeld, a civil rights attorney, who has represented clients involved in animal rights and environmental direct action. Since then, the government’s response has only intensified, he argues: “People are being attacked, detained and deported – if they’re lucky – almost for nothing, for political viewpoints and opinions and expressions that the government finds distasteful.”

San Diego was born in the progressive stronghold of Berkeley, California. His father, Edmund San Diego, was the respected city manager of Belvedere, a wealthy enclave on Marin county’s Tiburon peninsula. He fell into activism as a teenager: starting when he was 19 years old, he worked for two years at In Defense of Animals, a non-profit that campaigns against animal testing.

At the turn of the millennium, animal rights and environmental direct action were an integral part of the burgeoning anti-globalization movement that defined much of contemporary youth counterculture, particularly on the west coast. Information tables about the Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty campaign, veganism and forest defense campaigns were part of the landscape at punk shows, book festivals and raves.

It was through that subculture that young people were drawn to the underground of militant environmentalism and animal liberation, which had thrived since the early 1980s. “The major difference between the scene now and then is there were a lot of paper flyers, word-of-mouth actions, things that felt like a punk rock secret society and a cheerleading aspect where one city was trying to outdo each other in terms of direct action and sabotage,” recounted a former militant, whom the Guardian is not identifying because of fear of targeting by the Trump administration.

San Diego was well-known among the above-ground animal rights activists and participated in the formal SHAC campaign. “He was not a guy who was festering in the basement and building bombs,” Rod Coronado, a direct-action advocate and militant environmentalist who worked with San Diego on Huntingdon-related campaigning in California, told the Los Angeles Times in 2003. “He was not the person with the loudest, most radical voice in meetings, but he was active in demonstrations.”

Two former radicals involved in direct actions like freeing animals from testing labs or sabotaging testing companies in northern California during the early 2000s said that San Diego did not participate in such activities, to the best of their knowledge.

The first pipe bomb went off at 2.55am on 28 August 2003 outside Chiron Corporation’s headquarters in Emeryville. A second nail-filled explosive device went off at a separate building on Chiron’s campus around 3.59am. No one was injured in the explosions, which blew out windows and caused superficial damage to the office building. For weeks, authorities searched in vain for a suspect caught on grainy CCTV footage holding a bag outside Chiron. On 26 September, another pipe bomb attached to a digital timer exploded at 3.22am outside a building that houses Shaklee Corporation.

San Diego had been pulled over by a Pleasanton police officer at an on-ramp to the highway about half a mile from the Chiron campus about an hour before the device outside the Shaklee Corporation exploded. He was released, but the officer wrote up a field contact card with his information. Court records do not make clear why San Diego was pulled over, and the officer who made the stop has since passed away.

During their investigation following the explosion, federal investigators came across the card and put San Diego under 24-hour surveillance.

On 8 October 2003, San Diego drove from his two-story home in Schellville, Sonoma county, to San Francisco, tailed by an FBI team in a vehicle following his car and a fixed-wing surveillance airplane. Two former FBI agents who spoke to the BBC earlier this year said San Diego was being tailed in hopes that he would lead them to other violent animal rights militants. He drove west through fog-shrouded Marin county and across the Golden Gate Bridge, causing the FBI’s aerial surveillance to lose track of him. He drove to a busy intersection in downtown San Francisco, where he parked his car, left the engine running, got out and walked down the stairs into a Muni station. He was never seen again in the United States. His parents urged him to surrender in 2003, but their appeals did not land.

When FBI agents searched San Diego’s Schellville home and car later that week, they found copies of the animal rights magazine whose website posted claims for both bombings. Per federal prosecutors, the trunk of his car contained a mobile bomb-making kit, with copper coil, black PVC pipes, methyl ethyl ketone, aconite, adenosine triphosphate and a wire stripper. San Diego’s fingerprints were found on some of the chemical containers, authorities say.

In court this September, British crown prosecutors said a wire stripper found in his car was matched to crimp markings on copper wiring found in the debris from all three bombings San Diego is charged with.

In 2009, the FBI added San Diego to the agency’s Most Wanted list and offered a $250,000 reward for his capture, generating another burst of publicity. FBI graphics from the time show San Diego’s photograph featured alongside that of al-Qaida’s Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri.

After San Diego evaded US authorities, his trail went cold. Dana Ridenour, a retired FBI undercover agent who attempted to penetrate the animal rights world in northern California during the mid-2000s, recounted tracking San Diego’s whereabouts as part of her “domestic terrorism” assignment on a podcast this February.

“That was one of my missions, to try to ascertain where he was, if he was still in the United States. There was a couple of people that I kind of cozied up to that we thought may know where he was laying low,” Ridenour said, adding that she chased reports he was in Germany, Hawai’i and Massachusetts.

It was only after his November 2024 arrest in the northern Welsh hamlet of Maenan, more than 5,000 miles (8,000km) from California, that his life as a fugitive took shape. When arrested, San Diego possessed an Irish passport in the name of “Danny Stephen Webb”, with a date of birth eight months earlier than his own.

According to the Times of London, San Diego surfaced in Great Britain around February 2005, when he started work as an information technology expert with a digital startup firm in London. A decade later, he obtained another job as a Linux system administrator in a larger, Manchester-based e-commerce company. He moved to the remote, sparsely populated Conwy valley in the late 2010s, buying a detached home with a twin garage near the village of Treuddyn near Mold for £223,000 in cash in January 2018.

It’s unclear what ultimately gave San Diego away. Was it his second home purchase, in 2023, for which he obtained a £40,000 mortgage from the Nationwide Building Society? Or him joining Unity, the digital games company based in San Francisco – his first time working for a company from his birth country since fleeing the United States 21 years earlier?

Regardless, the FBI ascertained his true identity. He was arrested on 25 November 2024, with locals telling the Times there had been rumors that the village had been under surveillance by British authorities for months.

It is still unclear how San Diego made his way across the Atlantic Ocean and established a new identity, replete with documentation sufficient for him to obtain work. It is unclear whether his Irish alias enabled him to obtain a passport or travel outside the United Kingdom.

When arrested, San Diego denied his true identity but was given away by old tattoos from his radical days, including ink with burning buildings, a tree growing out of a road and a picture of a burning hillside with the inscription “It only takes a spark”.

Shortly after his arrest, former animal rights activist Peter Young told the Guardian the FBI twice asked him for information about San Diego’s whereabouts, most recently in 2019. “I think the theory of the FBI is that there’s this underground railroad for activists, fugitives, and that is really not the case. It really just comes down to who you know, in terms of your supporters, [but] there is no underground network,” he said. Indicted in 1998 over a string of fur farm raids across three states, Young served two years in federal prison in the mid-2000s after fleeing the US for Great Britain.

During extradition proceedings earlier this year in London, San Diego’s lawyers argued that the United States is no longer a country where the former activist can receive a fair trial.

“The issue of political interference in the trial process, or prison designation process, is a significant issue in this case,” barrister Mark Summers said at San Diego’s 8 September hearing, also noting the Trump administration’s systemic attacks on judges.

“In the system prevailing in America, Mr San Diego is a politically disfavored case.”

The charges against San Diego, his attorneys allege, are “stacked” in a manner that is designed to elicit plea agreements, in contravention of a 2018 federal law meant to decrease prison terms.

They also argue that if convicted, he faces serious risks of harm from other incarcerated people because he’s designated a “high-risk” prisoner by the Bureau of Prisons. The legal arguments against his extradition are structured around European court of human rights rulings about disproportionate sentencing, political prosecutions, conditions of detention and the possibility of receiving a fair trial, all of which they claim San Diego will not receive should he be returned to the United States.

The final days of evidence at San Diego’s extradition hearing will be 8 December, with closing arguments scheduled for 23 December. Senior district judge Paul Goldspring, the ranking justice at the Westminster magistrate’s court, is expected to rule on San Diego’s extradition early in January 2026.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  3 weeks ago

3 weeks ago

Comments