Place names are more than just labels on a map. They influence how people learn about the world around them and perceive their place in it.

Names can send messages and suggest what is and isn’t valued in society. And the way that they are changed over time can signal cultural shifts.

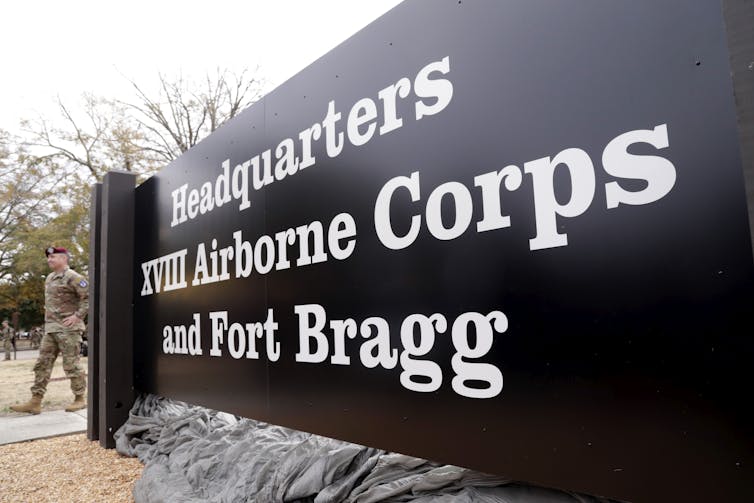

The United States is in the midst of a place-renaming moment. From the renaming of the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America, to the return of Forts Bragg and Benning and the newly re-renamed Mount McKinley in Alaska’s Denali National Park, we are witnessing a consequential shift in the politics of place naming.

This sudden rewriting of the nation’s map – done to “restore American greatness,” according to President Donald Trump’s executive order that made some of them official – is part of a name game that recognizes place names as powerful brands and political tools.

In our research on place naming, we explore how this “name game” is used to assert control over shared symbols and embed subtle and not-so-subtle messages in the landscape.

As geography teachers and researchers, we also recognize the educational and emotional impact the name game can have on the public.

Place names can have psychological effects

Renaming a place is always an act of power.

People in power have long used place naming to claim control over the identity of the place, bolster their reputations, retaliate against opponents and achieve political goals.

These moves can have strong psychological effects, particularly when the name evokes something threatening. Changing a place name can fundamentally shift how people view, relate to or feel that they belong within that place.

In Shenandoah County, Virginia, students at two schools originally named for Confederate generals have been on an emotional roller coaster of name changes in recent years. The schools were renamed Mountain View and Honey Run in 2020 amid the national uproar over the murder of George Floyd, a Black man killed by a police officer in Minneapolis.

Four years later, the local school board reinstated the original Confederate names after conservatives took control of the board.

One Black eighth grader at Mountain View High School — now re-renamed Stonewall Jackson High School — testified at a board meeting about how the planned change would affect her:

“I would have to represent a man that fought for my ancestors to be slaves. If this board decides to restore the names, I would not feel like I was valued and respected,” she said. The board still approved the change, 5-1.

Even outside of schools, place names operate as a “hidden curriculum.” They provide narratives to the public about how the community or nation sees itself – as well as whose histories and perspectives it considers important or worthy of public attention.

Place names affect how people perceive, experience and emotionally connect to their surroundings in both conscious and subconscious ways. Psychologists, sociologists and geographers have explored how this sense of place manifests itself into the psyche, creating either attachment or aversion to place, whether it’s a school, mountain or park.

A tale of two forts

Renaming places can rally a leader’s supporters through rebranding.

Trump’s orders to restore the names Fort Bragg and Fort Benning, both originally named for Confederate generals, illustrate this effect. The names were changed to Fort Liberty and Fort Moore in 2023 after Congress passed a law banning the use of Confederate names for federal installations.

Trump made a campaign promise to his followers to “bring back the name” of Fort Bragg if reelected.

To get around the federal ban, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth identified two unrelated decorated Army veterans with the same last names — Bragg and Benning — but without any Confederate connections, to honor instead.

Call it a sleight of hand or a stroke of genius if you’d like, this tactic allowed the Department of Defense to revive politically charged names without violating the law.

The restoration of the names Bragg and Benning may feel like a symbolic homecoming for those who resisted the original name change or have emotional ties to the names through their memories of living and serving on the base, rather than a connection to the specific namesakes.

However, the names are still reminders of the military bases’ original association with defenders of slavery.

The place-renaming game

A wave of place-name changes during the Obama and Biden administrations focused on removing offensive or derogatory place names and recognizing Indigenous names.

For example, Clingmans Dome, the highest peak in the Great Smoky Mountains, was renamed to Kuwohi in September 2024, shifting the name from a Confederate general to a Cherokee word meaning “the mulberry place.”

Under the Trump administration, however, place-name changes are being advanced explicitly to push back against reform efforts, part of a broader assault on what Trump calls “woke culture.”

President Barack Obama changed Alaska’s Mount McKinley to Denali in 2015 to acknowledge Indigenous heritage and a long-standing name for the mountain. Officials in Alaska had requested the name change to Denali years earlier and supported the name change in 2015.

Trump, on his first day in office in January 2025, moved to rename Denali back to Mount McKinley, over the opposition of Republican politicians in Alaska. The state Legislature passed a resolution a few days later asking Trump to reconsider.

Georgia Rep. Earl “Buddy” Carter made a recent legislative proposal to rename Greenland as “Red, White, and Blueland” in support of Trump’s expansionist desire to purchase the island, which is an autonomous territory of Denmark.

Danish officials and Greenlanders saw Carter’s absurd proposal as insulting and damaging to diplomatic relations. It is not the first time that place renaming has been used as a form of symbolic insult in international relations.

Renaming the Gulf of Mexico to Gulf of America might have initially seemed improbable, but it is already reflected in common navigation apps.

Read more: Yes, Trump can rename the Gulf of Mexico – just not for everyone. Here’s how it works

A better way to choose place names

When leaders rename a place in an abrupt, unilateral fashion — often for ideological reasons — they risk alienating communities that deeply connect with those names as a form of memory, identity and place attachment.

A better alternative, in our view, would be to make renaming shared landscapes participatory, with opportunities for meaningful public involvement in the renaming process.

This approach does not avoid name changes, but it suggests the changes should respond to the social and psychological needs of communities and the evolving cultural identity of places — and not simply be used to score political points.

Instead, encouraging public participation — such as through landscape impact assessments and critical audits that take the needs of affected communities seriously — can cultivate a sense of shared ownership in the decision that may give those names more staying power.

The latest place renamings are already affecting the classroom experience. Students are not just memorizing new place labels, but they are also being asked to reevaluate the meaning of those places and their own relationship with the nation and the world.

As history has shown around the world, one of the major downsides of leaders imposing name changes is that the names can be easily replaced as soon as the next regime takes power. The result can be a never-ending name game.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  3 weeks ago

3 weeks ago

Comments