The 24-year-old Afghan woman wants to become a surgeon – and she had set her sights on training in the US.

She wants to care for other women and girls, so they don’t have to be afraid to visit the doctor – so at least in one crucial aspect of their lives they won’t have to endure the unwanted advances, dismissive comments and blatant disrespect that she’s experienced from many of the men who have always surrounded her, first in her native Afghanistan and now in legal limbo in Pakistan.

“I hope a lot that I will be a doctor in the future. I don’t know it will happen, but I hope,” she said. “It means that a woman is powerful, that if she wants to do something, she can.”

Yet for the moment, she has no way to attend medical school anywhere. She can barely step outside the apartment in Islamabad where she and her two sisters, her teenage brother, and their mother spend each day terrified that police will arrest and deport them back to face Taliban rule.

Simply as a woman in the Taliban’s Afghanistan her lifestyle would be severely restricted, but as Christians the whole family would literally be in mortal danger.

Her family has documents from the United Nations Refugee Agency proving that they’re certified asylum seekers, and they were on the verge of getting the green light to come to the US.

But to the Trump administration right now, these plans don’t matter – despite volunteer groups in Texas preparing for months to welcome them.

To the police in Pakistan, where they are in exile, those UN documents don’t matter either. What matters is that the family is Afghan and is no longer wanted there.

“Everywhere is policed. Every day, police come to our house. It’s too difficult for us,” said the woman in an interview over Zoom. The Guardian is withholding the family’s identity while they remain at risk.

“In these days, we awake with a fear,” she said of her family. They have already been lying low in Pakistan for three years after fleeing Afghanistan.

A few months ago, it seemed as though the family was finally on the cusp of relief, soon to fly to east Texas.

“They were nearing the finish line. We didn’t have any certainty, they hadn’t actually been approved and travel wasn’t being scheduled yet. But we were right there – everything, all the screening, was done,” said Justin Reese, one member of a group of Texas volunteers who were getting ready to welcome the family.

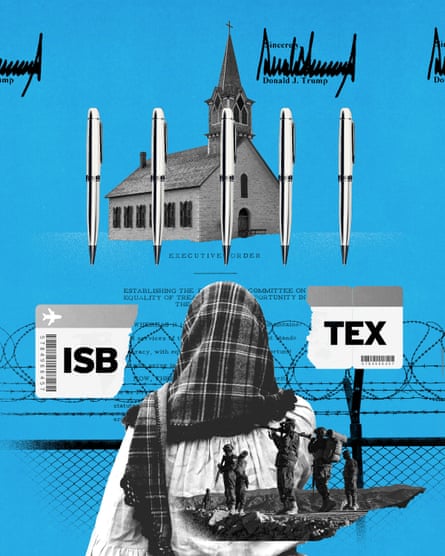

Then, on the first day of Donald Trump’s second term as president, one of his many immigration-related executive orders indefinitely suspended the US Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) – and with it, the family’s chance at reaching imminent safety.

“By every metric, they have played by the rules and they are being treated like this,” said Reese. “It’s very damaging to them individually, and it’s damaging, I think, to the future security of the US, for us to be seen as this mercurial, as this incoherent.”

A federal district judge temporarily blocked Trump’s effective ban on refugees coming to the US, offering those on the brink of resettlement a flicker of hope, but a circuit panel has now rolled back that decision, saying only people already approved must be allowed to come. And whether an administration ideologically opposed to refugee resettlement will resume the program at scale – or in any meaningful way – remains an open question, particularly after the state department has tried to terminate essential funding agreements with all of the US’s resettlement agencies for the entire fiscal year. That was even before the prospect of new Trump travel restrictions on Afghans entering the US, and before immigration officials suddenly paused green card processing for refugees already here.

“I don’t know how you get to a place of suspending refugee resettlement as policy without a series of ideological turns that I don’t understand how to unwind,” Reese said.

Before the ascent of Trumpism, USRAP enjoyed widespread bipartisan support for myriad reasons: its protection of American allies and related benefits to national security; its solidarity with “frontline states” such as Turkey and Colombia that are taking in so many of the world’s displaced people; its signal to other nations that the US cares about human rights.

In fact, even before the refugee resettlement program was written into US law, organizations cropped up across the nation in response to the atrocities of the second world war – and the US’s role in rejecting refugees early on who then became victims of the Holocaust. These agencies welcomed displaced people from around the world, many fleeing communism from the Baltic states, Hungary or Vietnam.

After Congress established a more universal, standardized refugee framework, general support for resettlement continued, even following the 11 September 2001 attacks that reshaped much of the US immigration system. Sometimes, scandals would arise within the program, but administrations would address them and move on.

Then, in 2015, Trump ran for president and soon started trumpeting a narrative that refugees posed a security threat to American communities, despite them being some of the most thoroughly vetted newcomers in the country.

“There [was] already a kind of deteriorating bipartisan support,” Yael Schacher, director for the Americas and Europe at Refugees International, the humanitarian organization, recalled of that moment.

By fiscal year 2020, the first Trump administration had gutted the US’s refugee resettlement infrastructure and set the annual ceiling on refugee admissions at 18,000 – the lowest cap on record.

When Joe Biden took office, his administration eventually rebuilt resettlement capacity in the US, with more than 100,000 people welcomed in his last full fiscal year in office.

To do so, Biden made innovations, such as an initiative called the Welcome Corps, which invited Americans and green card holders to form private groups and financially sponsor refugees for resettlement in the US.

“I think the idea of the Welcome Corps was that it was politically foolproof,” said Schacher, and that “because it relied on private funds and private individuals to step up … that these folks would push back against the Trump administration and make sure that folks still come. And they would step in if government funding was withdrawn. I think it remains to be seen if that’s actually going to work politically.”

Reese and his family knew that they wanted to participate in the Welcome Corps. A software developer by trade, he had spent the better part of a decade learning about the politics and policy of offering refuge.

Just before the coronavirus pandemic gripped the US, he traveled to Greece to serve in a refugee camp with 20,000 residents representing 40 different nationalities. The corner of camp where he volunteered hosted mostly Afghans, and he returned home to east Texas with new friendships and phone numbers from within that community.

So when Kabul fell to the Taliban and the US withdrew troops from Afghanistan in 2021, his phone started buzzing with alerts from worried Afghans whose loved ones were still stranded in danger. He sprang into action, attempting to cut through red tape to try to get desperate families in Afghanistan on US evacuation flights. It was frantic and exhausting.

“Everything felt like an inch away and then a mile away at the same time, because you just knew if you just were smart enough or well-resourced enough, then you could make this happen,” he remembered.

Simultaneously, the Afghan family of five he would eventually try to resettle through the Welcome Corps was fleeing Afghanistan for Pakistan. The Taliban’s return to power was the final straw that dashed any hope they had for stability in their homeland, though it was hardly their first brush with persecution.

As members of the Hazara ethnic community, their people had long been victims of massacres and genocides, including by the Taliban at the turn of the 21st century. Having converted from Shia Islam to Christianity, the family had been targeted by their neighbors, beaten and forced to move many times. And as a household in which the patriarch died about a decade ago, the women had been subject to constant unwanted attention and harassment from unscrupulous men.

“We miss, a lot, our country,” one of the daughters said. “We miss our memories that we had. But unfortunately we can’t go back because I have lots of bad memories from Taliban … situations, and it makes me sad.” As she described the family’s experience, she wept.

Her family met Reese in person when they were all in Islamabad in late 2023. Until then, they had been names on a list for Reese, names he was still trying to help find refuge. After getting to know the family face to face, he wanted to bring them to his own community, where he thought their life experiences would resonate with people.

He found willing volunteers back in east Texas. With 10 members, Reese’s Welcome Corps group is far larger than required and includes a veteran who served in Afghanistan, a missionary’s kid who grew up in Afghanistan and Pakistan, a couple whose children work with Afghans abroad, and others uniquely equipped to help.

Offers of housing and other support flowed in. And Reese’s commitment to sponsor the Afghan family made a huge difference in their lives, even as they remained in a precarious situation abroad. They suddenly felt as though they were waiting in Pakistan for a reason, and they stopped worrying as much about their future while imagining safety together in the US.

“It made my family so happy,” one of the daughters said. In Texas, she hoped, “we can continue our studies and we can continue our lives without any worries”.

Now Reese’s garage is full of donated household items from an online wishlist to outfit what would have been the family’s new home in Tyler, Texas. It’s unclear when or if the family will ever arrive – news Reese had to deliver personally.

“I have a hard time talking about how it made us feel without being angry because I do feel that it’s not just unnecessary and harmful, but strategically incompetent,” he said. “I don’t believe that anybody involved in turning [USRAP] off had to deliver phone calls like the ones that we had to over the last few weeks.”

Despite the setback and the increasingly serious threats of deportation the family faces in Islamabad, one of the daughters expressed gratitude for “brother Justin”, as she calls Reese, and appreciates at least hearing an update on their case.

Trump’s actions have made her “sad, but I hope”, she said, adding: “I have hope in my heart that this program will open again.”

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  21 hours ago

21 hours ago

Comments