In all the arguments over whether President-elect Donald Trump’s choice for director of national intelligence is fit for the job, it’s easy to lose sight of why it matters.

It matters a lot. To speak of telling truth to power seems terribly old-fashioned these days, but as a veteran of White House intelligence operations, I know that is the essence of the job.

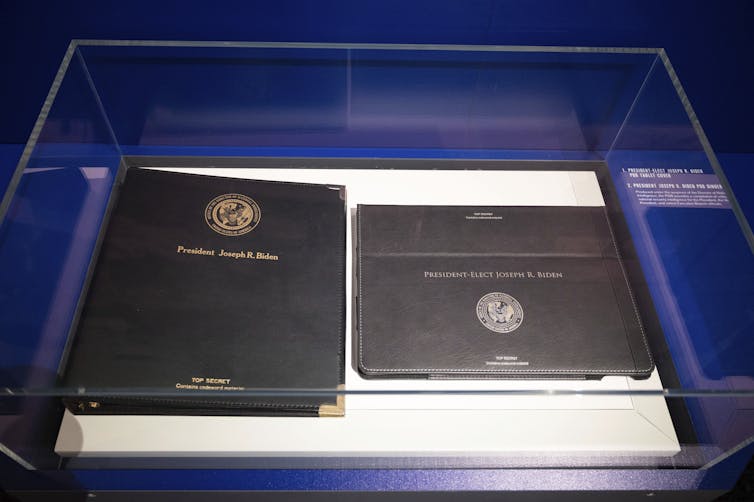

The director of national intelligence is the president’s principal adviser on intelligence, though the CIA director has remained somewhat co-equal in that role. The director of national intelligence is responsible for both the President’s Daily Brief, where the most crucial and sophisticated intelligence is presented, and for the work of the National Intelligence Council. Most of the President’s Daily Brief items are still done by the CIA, but the director of national intelligence or their deputy briefs the president, daily in most administrations but one or two times a week in the first Trump administration.

The issues in those briefings lean toward the immediate and tactical: What is the situation on the ground in the Ukraine war? If action X is taken, how will Russian President Vladimir Putin respond? But intelligence strives to push presidents and their colleagues to think more strategically: What are the implications of hypersonic missiles? What is the trajectory of the relationship between Russia and China? What are China’s geostrategic objectives, and what is the role of the Belt and Road Initiative in that vision?

9/11 led to intelligence changes

The current director of national intelligence is Avril Haines, who is my friend and former colleague from when she was the deputy national security adviser in charge of the National Security Council policy committees and I was chair of the National Intelligence Council, providing the intelligence support to those committees.

As director of national intelligence, Haines sits atop the 17 agencies that make up what is called the U.S. intelligence community. She does not run those agencies. Nor does she have full control of their budgets.

Rather, the director of national intelligence coordinates them, which sometimes seems like the proverbial herding of cats. She assembles a combined budget for intelligence, but many of the big agencies, such as the National Security Agency, which makes and breaks codes and intercepts signals of interest, belong to the Pentagon.

The creation of the director of national intelligence position was a direct result of the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

The report of the 9/11 Commission was vividly damning about the failures of communication between agencies in the run-up to 9/11. In meetings in New York that summer, CIA and FBI officers were literally unsure what they could tell each other: The former wondered whether the FBI people were really cleared to hear this, while the latter feared that talking might blow a case they were working on. That lack of coordination played a role in letting the plotters slip through intelligence, often in plain sight.

The result of the commission’s work was the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, which created the director of national intelligence position.

Before that, the director of central intelligence wore two hats, as the director of the Central Intelligence Agency and loose coordinator of the broader intelligence community. Hardly surprisingly, directors of central intelligence spent most of their time running the CIA, for that was the source of their troops – and their troubles when they arose. A score of blue-ribbon panels over 50 years had recommended breaking the director of central intelligence’s conflict of interest – coordinating agencies and their budgets while running one of them – and creating a director of national intelligence position.

James Clapper, the director of national intelligence for whom I worked as chair of the National Intelligence Council, constantly emphasized “integration.” Across agencies, integration mostly means talking to each other and sharing information. This works against the natural tendency to scoop your colleagues.

Across disciplines, integration means better aligning what information intelligence agencies collect with what analysts need.

How integration works

If presidents want to know what the CIA thinks about a particular issue, they can simply ask. Usually, though, the question is what does the intelligence community think, and then the question goes to the National Intelligence Council, the director of national intelligence’s interagency group for intelligence analysis.

The National Intelligence Council is organized like the State Department, with officers for regions and functions. Once a question has been presented, the relevant national intelligence officer will convene his or her council colleagues from the other agencies. They will argue about the answer to the question, a process sweetly called “coordination,” then agree on the answer. If need be, the process can be done in a few hours. Major strategic analyses – national intelligence estimates – like one done in 2022 on the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic out to 2026, may take months. In all cases, though, the analysis carefully records where there are differences of view in the intelligence community.

In my last year chairing the National Intelligence Council, of the 700 or so analyses we did, about 400 were responses to questions – called “taskings” in governmentese – from the national security adviser or one of the deputies.

National intelligence officers are national experts from inside or outside federal government, and their deputies – the heart and soul of the NIC – are all assigned from intelligence agencies. The largest number come from the CIA, but I worked with a cyber analyst from the Secret Service and a wonderful analyst from the New York Police Department.

Resolutely nonpolitical stance

What was striking then and has struck me both times I’ve had the privilege of running a U.S. intelligence agency is the dedication of the officers. They work for the nation, not for a political party or ideology. As chair of the NIC, I had no idea of the politics of my people, save for the several closest to me. For them, telling truth to power is not a slogan. It is what they do. They are always worried about “politicizing” – producing an assessment to suit a policymaker’s preference or, worse, being pressured to do so.

The president’s daily briefers, for instance, give up a year of their lives to come to work at 4 a.m., learn their briefs and then fan out across Washington to brief senior officials. They like being “on the team” of the person they brief, but they become uncomfortable if the conversation turns political. The director of national intelligence sets the tone for that resolutely nonpolitical stance and polices it through principles articulated in the agency’s analytic integrity and standards. As chair of the NIC, for instance, I’d receive regular assessments of both the quality of our analyses and whether we risked becoming “politicized.”

For their part, do politicians and agency leaders like it when their pet projects are assessed by intelligence as unwise or infeasible? Of course not. I’ve been on that side of the intelligence-policy divide as well. But the United States is much the better for it.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  7 hours ago

7 hours ago

Comments