From his father’s strawberry farm in central California, Tomás Diaz noticed a border patrol vehicle driving toward a field of workers. Diaz, himself Mexican American and a US citizen, yelled in Spanish: “Run for your life! That’s immigration!” As the men scattered, the agents grabbed whom they could. In the chaos, six workers escaped, and Diaz was detained for interrogation. “Why did you yell at the Mexicans to run?” an officer pressed. “No reason at all,” Diaz calmly replied.

This did not happen yesterday, but in 1953. Driven by fears of border infiltration by communists and “criminal” and “diseased” migrants, the Immigration and National Service (the Department of Homeland Security’s predecessor) carried out “Operation Wetback” from 1954 to 1957. Border patrol officers raided public spaces, workplaces and homes and formally deported about 400,000 Mexicans (hundreds of thousands more repatriated out of fear).

More than 70 years after Operation Wetback, the mass deportation campaign orchestrated by Trump, homeland security (DHS) adviser Stephen Miller and DHS secretary Kristi Noem is using Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice) officers to conduct Orwellian raids. Trump’s administration knows that targeting workers in the food chain is the easiest way to reach Miller’s quota of 3,000 arrests a day. Labor department data affirms that 42% of US farm workers lack proper documentation. Ice agents are rushing into fruit orchards, vegetable fields, dairy barns, processing plants and restaurant kitchens to arrest people on the spot.

The consequences of these raids will be profound in our food labor system and greater society. First and foremost, these raids are traumatizing people. Many arrestees are “disappeared”, their locations unknown by loved ones and lawyers.

Second, the raids will affect summer food chains and other industries throughout the year. The juicy watermelons and peaches, berry pies, barbecue, ice-cream and lobster rolls we are currently enjoying come from the labor of a heavily immigrant workforce. Almost every bit of American food and drink passes through the hands of an immigrant, and the DHS is denying this reality while terrorizing food workers with brutal efficiency.

In the seafood industry, Latin American and Caribbean workers in fish-processing plants in New England and on the Chesapeake Bay and the Gulf Coast ensure cod, crawfish, crab, scallops and lobster get to our markets and restaurants. An early Trump 2.0 raid targeted a seafood depot in Newark, New Jersey. Without warrants, agents demanded documentation from workers who looked Latino, and detained three immigrants and the warehouse manager, a Puerto Rican veteran who was eventually released but distressed that his citizenship and military service meant nothing. In New Bedford, Massachusetts (the nation’s highest-value fishing area), at least two dozen Guatemalan men have been taken. Latin American and Caribbean workers stepped into New England’s seafood industry at the turn of the century, a critical juncture when the children of Euro American fish workers rejected their occupational inheritance. If these workers are deported in large numbers, seafood circulations will decline precipitously across the nation and globe.

Summer ice-cream is made possible by the milking labor of (mostly undocumented and male) Latino dairy workers. In April, a raid occurred at a dairy farm in Vermont, a US state that would topple economically if not for milk’s production. Sixty-eight per cent of the state’s milk (and 43% of New England’s milk) comes from farms reliant on immigrant workers.

Enjoyed meat at a Fourth of July or weekend barbecue? A whopping 71% of animal-processing workers in the US are immigrants from Latin America, Asia and Africa. When Ice agents raided the Glenn Valley meat-processing plant in Omaha, Nebraska, and detained 76 workers, they took half of the plant’s workforce. Though Omaha has been a home for Mexican meatpackers for more than a century, the local police and sheriff cooperated with Ice dragnets by blocking traffic around multiple production plants.

Raids on food workers in California (which provides a third of the vegetables and more than half of the nation’s fruit and nuts) have gone the most viral. Video captured a fieldworker being chased down in the fog, while berry and citrus workers were harassed across three counties. Ice agents raided a grocery store; grabbed a tortilla truck driver; and arrested a female street vendor outside a Home Depot who held desperately onto a tree as bystanders filmed and yelled: “They’re kidnapping her!” It’s already happening, but food sellers in our informal economy will stop working in public in greater numbers.

Meanwhile, in brick-and-mortar establishments, Ice detained employees at nine restaurants in Washington DC; an Italian restaurant in San Diego; two Mexican restaurants in the Rio Grande Valley; and a Mexican restaurant in Pennsylvania. Food workers are often rendered invisible in spaces like fields, warehouses and kitchens. Trump’s administration is hoping that this food precariat is expendable enough that Americans won’t care or fight back against these workers’ arrests and detentions.

They’re wrong. Food workers are increasingly visible as the public records and spreads word of Ice incidents. Protesters showed up at the Omaha meat plant, and locals decried the arrest of a beloved Salvadoran bagel shop manager on Long Island, New York. Chilling videos of Ice agents invading private homes and smashing car windows to grab Latino drivers are inspiring popular backlash. And, as in the 1950s, US-born Latinos realize the hunting of “illegal” bodies leads to their own racial profiling.

In the 1950s, many agricultural employers railed against the INS and border patrol for deporting undocumented workers, claiming citizens were too unavailable or unreliable (in reality, this was often a union-busting argument). Today, food industry bosses are similarly pushing back against government. Glenn Valley owner Chad Hartmann accused the federal government of traumatizing his employees and failing to improve the E-Verify system that checks immigration status. The dairy industry has called out the deportations as myopic and reckless. Employers surely remember the first year of Covid, when food labor flows halted. Foreign workers were held up or quarantined at the border, while some US citizen farm workers stayed away from harvesting sites for fear of contagion and death.

Suddenly remembering his agribusiness donors, Trump declared a stop to immigration raids in the food industry on 12 June. Five days later, DHS leaders reversed Trump’s reversal, telling Ice agents to carry on. This whiplash reveals the administration’s internal dysfunction and callous denial of immigrant workers as fuller human beings with longstanding ties to the United States. Their ideal is a white America, with foreigners used for labor but considered return to sender at a moment’s notice.

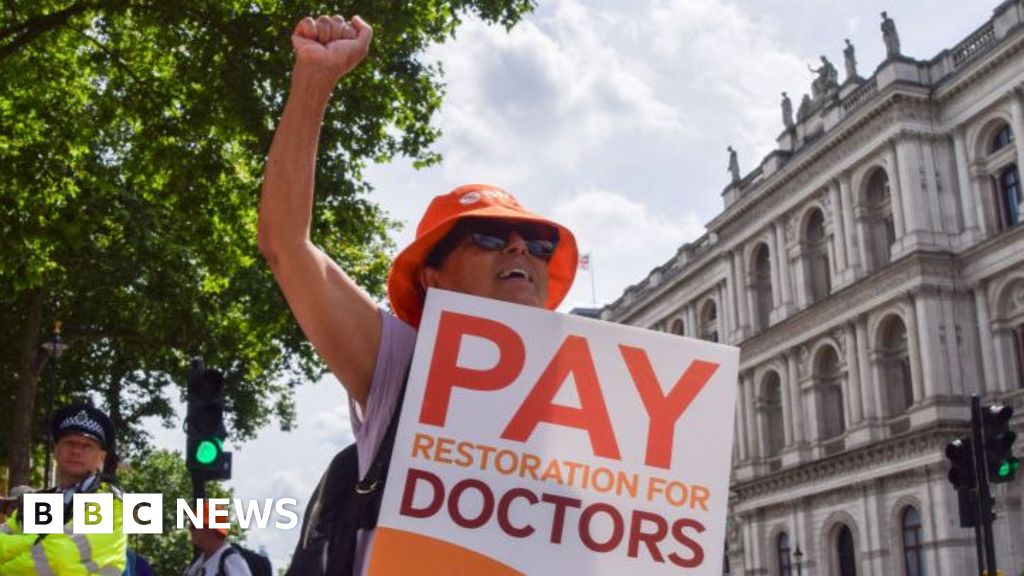

What can the past tell us about what’s to come? Consumers will feel the financial pinch first, and growers will blame increasing workforce instability and losing time on training new employees. Agriculture scretary Brooke Rollins’s ridiculous idea of using Medicaid recipients as farm workers will likely be supplanted by Trump’s expansion of the H-2A visa program. From 1942 to 1964, the bracero program (which offered around 5m labor contracts to Mexican men to work in US agriculture for six to nine months at a time) was shored up as the legal solution to the “wetback” crisis. The H-2A program is bracerismo reincarnated; it binds a guest worker to one employer for the entirety of their contract, even if problems arise regarding wage theft, substandard living conditions or threats to physical safety. Swift backlash against grievances keeps guest workers feeling silenced and chronically deportable.

Cruelty and dehumanization are the points of Trump’s immigration schemes. We must not lose sight of this while protesting raids in food spaces. Immigrants’ value lies far beyond “doing the jobs Americans won’t do”. Their mistreatment and unfreedoms are inextricably bound up with, and will affect, those of other Americans. Most recently, Maga acolyte Laura Loomer’s X post about feeding the nation’s 65 million Latinos to alligators in the Everglades generated loud condemnation. The US has long consumed the labor, cuisine and culture of Latinos, both citizen and immigrant. Loomer’s rhetoric takes that consumption to a grotesque level of real, not just imagined, violence.

Today’s Ice raids are an echo of the past, and stem from the Trump administration’s racialization of Latinos. At best, they can be instrumentalized for labor; at worst, they are a perpetually foreign population to be eradicated. Through showing solidarity with the diverse people who hold our food chains together, the public can give the Trump administration a much-needed reality check that it can’t talk (or eat) out of both sides of its mouth.

-

Lori A Flores is a professor of history at Columbia University and the author of Awaiting Their Feast: Latinx Food Workers and Activism from World War II to Covid-19

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  7 hours ago

7 hours ago

Comments