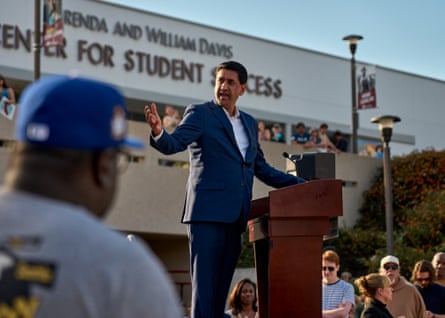

It was mid-December, and Ro Khanna was watching the calendar. The 19 December deadline for the justice department to comply with a new law the California representative wrote was ticking closer – and his bill was already forcing sealed documents about Jeffrey Epstein’s sex-trafficking operation into full view.

In the weeks leading up to the deadline, three federal judges in Florida and New York had reversed years of secrecy, releasing grand jury testimony they had previously kept sealed. And when the deadline arrived, while the justice department didn’t release everything, thousands of new files, connections and photographs began to complete the picture on what Khanna calls “the Epstein class … rich and powerful men who still have buildings named after them, who still are on corporations, are still in positions of prestige, who engage in heinous conduct.

“I believe that this is going to be a reckoning for America,” Khanna said during an interview in his office.

The Epstein Files Transparency Act took just five months from concept to passage, unusually fast for a political body where most legislation dies quietly in committee. It was not beginner’s luck for Khanna. The forced release of the Epstein files is just the cherry on top in a series of Khanna’s major improbable wins that have crossed party lines over the years, which include the passing of the first war-powers resolution through both chambers of Congress in history and the passage of the largest industrial policy bill in generations.

The California Democrat’s theory is simple, even if it upends decades of Washington thinking: finding common ground doesn’t just happen in the center. It also happens at the edges, where populist anger on the left and right finds new avenues to align against a system both sides believe has failed them. “The places where you can find common ground is not on incremental policy of how we extend the tax credits for healthcare,” he said.

Consider the 2019 Yemen War Powers Resolution, which marked the first time Congress passed a war -powers resolution through both chambers to direct an end to US involvement in an ongoing conflict. Khanna has cited that passage as an early sign that bipartisan agreement on restraining executive war powers was possible, even though the measure was ultimately vetoed by Trump and did not take legal effect.

At that time, Khanna, Senator Bernie Sanders and the Republican representative Thomas Massie built what seemed like an impossibly odd coalition: progressive Democrats who opposed endless wars and libertarian Republicans skeptical of foreign intervention.

“The Republicans were in charge of Congress, the Republicans were in charge of the Senate,” Khanna recalls. “And then we actually did pass the war -powers resolution, Sanders and I, to stop the refueling of Saudi planes that were bombing Yemen. We had Trump as president, and we had a Republican Senate, but I built an alliance at the time with people like Thomas Massie, Mark Meadows, Rand Paul and Mike Lee.”

The turning point, Khanna explained, was the assassination of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi – an event that “helped catalyze the Republicans to be willing to get on board”. But the groundwork had been laid for months. “It requires all of these things that also require months, if not years, of effort,” he says.

The Chips and Science Act took even longer: two years of work that began in the first Trump administration in 2020 with the former Republican congressmember Mike Gallagher, Republican senator Todd Young and Chuck Schumer, the Democrats’ leader in the Senate. The bill initially stalled, and finally passed in 2022, bringing semiconductor manufacturing back to American soil, with factories now rising in Ohio and Arizona.

“It took Biden’s election. It took two years of work and … a lot of work with getting Republicans on board on industrial policy,” Khanna said, pointing at the Publius award hanging in his office, which is awarded by the non-partisan Center for the Study of the Presidency and Congress for best exemplifying bipartisanship.

Then there’s the Epstein case. First, Khanna introduced an amendment to release sealed files related to Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell’s sex-trafficking operations. He got one Republican vote in the rules committee – Ralph Norman. That was enough to get the ball rolling.

“Thomas Massie said: ‘Well, if you can get one Republican in the rules committee, maybe we can get more Republicans,’” Khanna recalled.

Despite all those wins, Khanna doesn’t have the distinction for being the most bipartisan member of Congress. In fact, he sat somewhere in the middle of the 436 representatives ranked in the Lugar Center’s 2023 bipartisan index, the last time it was released.

If you’re looking for a pattern to his votes, he’ll give you one: “Good jobs at home, no dumb wars overseas, accountability for elites.” These are his three pillars for what he calls a “modern FDR coalition” – a realignment that brings together progressive voters and what he terms “disaffected Maga voters”.

It’s an openly populist pitch, one that rejects what the Democrat sees as the failed deal-making between the parties of the past several decades. “The traditional coalition of neoliberalism, which was an overreliance of the faith in the market,” he argues, “was accompanied with the militarism overseas, had failed a lot of people, including many Trump voters.”

This isn’t about splitting the difference on tax policy or finding modest compromises on healthcare subsidies, he says: “This is, how do we build coalitions to fundamentally change the economic and political structure that has shafted the working class?”

The formula has led him to unlikely partnerships. He’s written op-eds with Rand Paul about ending overseas wars. He’s worked with Marco Rubio, while he was a Florida senator, on creating a White House economic development council. Before she began her congressional exit, he was talking with Marjorie Taylor Greene about expanding Medicare to people 50-55 and working on a cost of living resolution.

“I developed a relationship with her, so, you know, but now I look for other partners,” he said.

Ask Khanna about the mechanics of bipartisanship success and he gets specific. First, master the institution: “You’ve got to really understand the rules of the institution and the procedure of the institution. You can’t be effective here without understanding the institution.”

Second, build real relationships: “You’ve got to have people on the other side. It doesn’t have to be a lot, but a few who you develop relationships of trust, where you can really text each other, call each other, be able to do more than just put your name on a bill.”

He estimates he has these kinds of relationships with “a handful” of Republicans – “people who really I can go out and have a meal with, or will take my call so that you can build some momentum”.

The Epstein act succeeded so quickly, Khanna argues, partly because of what he calls “muscle memory” – the trust he and Massie had already built working on foreign policy. “Massie and I had been working together on other issues,” he explains.

But he’s candid about the odds. When asked whether these bills ever almost fell apart, he laughs: “All of them almost fell apart. I mean, the probability of passing a bill is stacked against you.” He estimates he gave each bill a 5% chance of success when they started.

Even with Republican partners on board, there were obstacles. On the Epstein act, “the president, President Trump, was campaigning and threatening people”, Khanna says. Within his own party, he “had to convince my own leadership that this was a worthwhile fight”.

That’s where establishment politics mattered. “Hakeem [Jeffries] and his team, [executive director ] Gideon [Bragin] on his team, they’re very savvy, and so they understand, follow the cultural trends,” Khanna says of the House minority leader. “This is an example of why having younger, modern leadership is important for a party, because they jumped on it right away.”

With three major wins, clear pillars of agreement and trusted partners across the aisle, it’s a feelgood story of how politics could work differently. Yet, his theory assumes populist anger can overcome deep disagreements about solutions.

A progressive wanting Medicare for All and a Maga Republican wanting to dismantle agencies might both oppose “endless wars” but they are fighting different wars at home.

Then, there’s the question of replicability. Khanna is himself a former Silicon Valley executive with degrees from the University of Chicago and Yale, representing one of California’s wealthiest and bluest districts. He has the luxury of not worrying about leftwing primary challenges when working with the Freedom caucus.

But Khanna would argue this misses the point. His wins don’t only come from policy alignment, but also from shared moral conviction: the Epstein act worked because both sides genuinely wanted to hold powerful predators accountable.

“One woman came up to me when I was back home and said: ‘You know, I’m a victim of sexual assault, and I finally feel heard by my government,” he said.

Whether that anger and disillusionment with the system could scale to build a “modern FDR coalition” without a unifying crisis like the Depression remains an open question.

For now, Khanna keeps working his theory. He’s currently pushing a bipartisan war-powers resolution to prevent regime change in Venezuela, working again with Republicans to constrain executive military action.

The chances it goes through may not be the best. But he’s passed bills with worse odds before.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  3 weeks ago

3 weeks ago

Comments