Daniel Kamalić was born and raised in New York City, where he spent his summers riding his bike around Brighton Beach before pedaling home to his “Brooklyn Jewish” mother and his “smooth talker” father. He went out for Cub Scouts and soccer before realizing, during his time studying at MIT, that he loved sailing most of all. Now 48, he is a professional tenor with the opera, performing in and around New York.

Kamalić never considered that he might want to be anything but American – why would he? His life was shaped by the freedoms and opportunities that his father, Ivan Kamalić, risked everything for.

In the 1960s, after Ivan’s family fell out of favor with the communist regime in Yugoslavia, Ivan and a friend set sail on the Adriatic in a stolen boat with sails painted black – they were not yet 20 years old. When the boat sank, they were picked up by an Italian freighter and brought to a refugee camp. Ivan eventually made it to the US, but he didn’t talk much about his country of birth, which, after decades of oppression and war, declared independence as Croatia in 1991 and joined the EU in 2013. “My father always just said he came here for french fries, blue jeans and rock‘n’roll,” says Kamalić.

Kamalić visited Croatia in 1998 and was thrilled to meet family members who were artistic like him. After Ivan died in 2011, those ties grew stronger. But it wasn’t until a second Trump administration looked probable that Kamalić got serious about gathering paperwork for dual citizenship with Croatia, a right inherited from Ivan. By the time he filed this spring, he was worried about declining arts funding under the Trump administration affecting his career.

The whiplash nature of the news cycle in 2025 alarmed him, too: rising antisemitism experienced by Jewish Americans after 7 October 2023, immigration raids resulting in the forced removal of thousands from the US, the arrest of Palestinian rights activist and green card holder Mahmoud Khalil, who missed his son’s birth while in ICE detention, cuts to Medicaid … none of the protections Kamalić had taken for granted in the US felt certain anymore.

“The more that happens, the more I worry about it being in the realm of possibility: to need to become a political refugee from the US, the way my father was a political refugee from Yugoslavia,” says Kamalić.

“I want to get my Croatian citizenship so I can travel and work in Europe without restrictions. And if worst comes to worst, I want that escape route.”

Unexpected emotions

Just the idea used to be absurd – that the US may not be the best place for a natural-born US citizen. But more Americans than ever are eyeing the right to dual citizenship by descent.

“The political instability in the US in recent years, along with Covid, has brought home to people that there might actually be a reason to live someplace else,” says Peter Spiro, a law professor at Temple University in Pennsylvania and author of several books about citizenship. “It has really highlighted the insurance value of a second citizenship. That’s new for Americans – this idea of having a plan B.”

If you have a parent or grandparent who was born in a country other than the US, there’s a good chance that their citizenship could become yours through jus sanguinis, or the “right of blood”. Many countries allow dual citizenship, including the US, most of Europe and Africa, and parts of Asia and the Middle East, and while qualifying requirements vary considerably, most permit citizenship to be passed down through a parent, maybe a grandparent. Compared with immigration processes for migrants or newlyweds, which come with expensive visas, years-long qualifying periods or steep investment requirements, citizenship by descent is a relatively simple way to pick up a second passport for those lucky enough to qualify. Aside from fees for document copies and notarizations to prove a familial claim, the main requirement is patience to tackle bureaucracy. (Speaking the language of the target country helps.)

Americans who recently decided to pursue this birthright described to the Guardian different tipping points. For some it was the awareness that their reproductive rights were no longer secure or the fear that their trans child’s rights would not be respected, while for others it was the feeling that working hard wasn’t enough to lead to a good life in the US.

“I always felt that America tried to move forward and progress. Maybe not as quickly as everybody would like, but we were moving in the right direction,” says Hollis Rutledge, who is considering relocating to his grandparents’ homeland of Mexico. He described his America as above all a place of welcome, recalling the line “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free”. “But this is disappearing, and it’s really made me question: what is a nation? What is a country?”

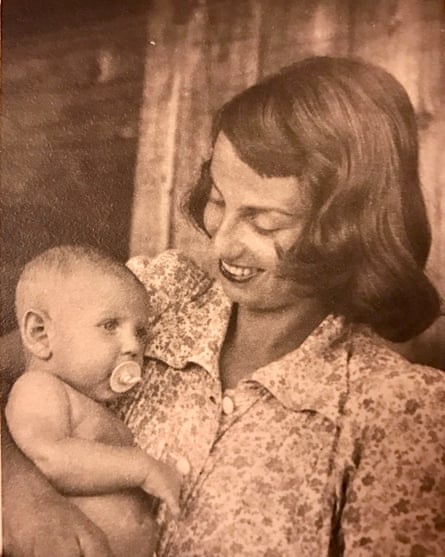

What starts as a straightforward plan to broaden one’s options tends to stir up unexpected emotions. Seeking out dual citizenship by descent is to question your sense of patriotism and belonging. Every journey comes with a story of an ancestor who left their country for opportunity or survival, not so many generations ago – these are not tales from a sepia-toned photograph. The price of admission is pledging allegiance to the same country that might have persecuted a father or grandmother.

Texas-born Rutledge, 48, recently secured dual citizenship with Mexico through his mother, whose parents were born there. At first it was the US economy that inspired Rutledge, who works in sales and marketing – prices had been going up. “I thought it might not be a bad idea to have that extra citizenship in my pocket, because Mexico has a pretty decent cost of living. Your retirement dollars can definitely stretch further south of the border,” he says.

Rutledge’s grandfather, Oscar Ochoa, became naturalized after serving in the US military during the second world war: “He wanted to give his kids a better life here in the US.” As Mexico didn’t allow dual citizenship at the time, Oscar had to renounce to become an American. This was a hard bargain – when his wife, Dora Garza, came to the US, she refused to naturalize until Mexico opened up for dual citizenship in 1998. Dora, now 102, is thrilled that her grandson has become a citizen of the country she loves: “When I first told her about it, she was in tears of joy.”

In the past year, Rutledge’s motivations for dual citizenship have increasingly become political. Rutledge was shocked when hundreds of tons of US Aid food was destroyed this summer rather than distributed to people who needed it. He is also thinking of his wife and four children: “They’ve been rolling back rights for women. They’ve been pushing back on LGBTQ+ rights” – Rutledge has a trans child. “I want my children to have the freedoms and opportunities that I feel should be afforded to them, and the US just doesn’t quite fit the bill as much as it used to.”

Rutledge’s children are actually triple citizens now, as his wife was born in Canada. “The only words they will ever hear at a border crossing in North America will be: ‘Welcome home.’”

‘A lot of disillusion’

Dual citizenship used to be frowned upon in the US. “The standard comparison was bigamy,” says Spiro. “Certainly before world war two, having dual citizenship wasn’t something you would advertise.” It was perceived as disloyal, and tricky in the age of obligatory military service, but with time the social stigma has fallen away. Now it’s an aspirational goal for 66% of US gen Z and millennials, according to a Harris Poll survey from earlier this year, due to “expanded travel freedom, economic benefits, and cultural connections”. The desire to migrate among younger Americans has quadrupled in the past decade, according to a recent Gallup poll, with 40% of women aged 15-44 saying they would move abroad permanently if they had the option.

Sixteen-year-old Kyla Shannon’s aunt Rose recently helped her get a German passport through her Jewish great grandmother, who fled Germany in the run-up to the second world war. Shannon, who is from Oregon, feels more connected to her ancestors now – “but I think this can also be about our future and not just about our past,” she says. She is looking into options for college in Europe, and her friends are a little jealous that she can go live there so easily. “There’s a lot of disillusion with the idea that America is a place where anyone can succeed. With the way things are set up, it doesn’t feel like an equal opportunity country, or even a country that treats everyone decently.”

Shannon is quick to add that she doesn’t think Europe is a utopia either. “It’s just really neat to have this other pathway I could take.”

The US does not have a central registry of Americans who are dual citizens, including by descent. But according to data gathered by Al Jazeera from legal outfits facilitating the process, US applications for citizenship by descent may have grown by 500% since 2023. In May the UK reported the highest number of Americans applying for British citizenship since records began 21 years ago, with the majority using family links. Spiro says it’s “absolutely clear” that there’s been a “dramatic” increase in Americans seeking these familial ties.

The US once provided refuge for Mariam Diop’s family, who arrived during a time of political upheaval in West Africa. Now Diop, 24, is seeking dual citizenship with Senegal, her mother’s home country. (She asked for a pseudonym due to safety considerations.)

Diop says her Ivy League humanities degree gave her “a deep understanding of how intergenerational privilege and white supremacy functions” in the US. Having watched her mother struggle to find work in her field despite having a PhD, she says it will be difficult to get ahead on grit alone if you are Black with no family connections. She also thinks her generation’s been handed a raw deal – “[Gen Z] was sold the idea that if you go to college and work hard, you’ll be able to own a home, retire at 65, all these things”– with little hope of relief from US politicians, who she describes as “tribalistic” and uncaring.

“I feel sadness and grief at the direction of the country,” she says, her voice shaking a little. “I just don’t think it’s the right place for me right now.”

Still, Diop, who was born in the DC area, fields a lot of questions about why she’d want to move to West Africa. “I don’t consider this a step back … My mom says: ‘The work and sacrifices I made were for you to have choices in life.’” Besides, Diop is young, debt-free, with no children. Maybe this is the right time to use her education to help build the region’s future.

“There’s a powerful move within several West African nations around self-sovereignty,” says Diop. “The story is not just about people starving and sadness and dirt … I’d like to use my voice to [help] change the narrative.”

A second passport represents the knowledge that another country accepts you as an official citizen, and welcomes you to come and make a life. This is a strange feeling for Rose Freymuth-Frazier, Shannon’s aunt, who will soon visit Germany for the first time as a new dual citizen through Article 116, a law that restores citizenship for people who were deprived during the Nazi regime and their descendants. Freymuth-Frazier’s grandmother, Barbara Freymuth, was stripped of her German citizenship because she was Jewish.

Barbara left her homeland as the Nazis started encroaching in the 1930s, initially going to Switzerland before making it out of Europe in 1940, first going to the Dominican Republic and then to the US. She had never felt culturally Jewish but was “German to the core” – until she wasn’t. “She was run out of her country, the country she identified with and loved.”

This all felt like a long time ago when Freymuth-Frazier, who is 47 and a painter, looked to Article 116 to pursue German citizenship before the pandemic from a desire to connect with her family roots. “But I feel like the world has really changed,” she says. “I’ve had this feeling since 7 October. I live in New York near Columbia University, and literally underneath our windows [we hear] anti-Israel chants. It’s unnerving.” While Freymuth-Frazier’s life today is very different from Barbara’s in the 1930s, she’s been going through her own reckoning with her identity and “what it means to be Jewish in this world.” And unlike Barbara, she enjoys a freedom of movement.

Still, Freymuth-Frazier found it strange to see her nationality listed as Deutsch – “as I’m clearly American, born and bred” with a “wild, rough-and-tumble American upbringing” in northern California.

“I do have mixed feelings about it. My grandmother didn’t go back to Germany – she was done,” she says. “I don’t know the first thing about being a German.”

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  2 weeks ago

2 weeks ago

Comments