In one suburb of Minneapolis, the superintendent spends each school day driving to her district’s schools to track federal agents. Across the metro, in another suburb, a Latino church organizes food donations to deliver to thousands of families staying at home out of fear of immigration agents.

In town after town around Minnesota, federal agents have picked up immigrants and taken them away from their communities.

In the denser urban core, dozens of observers often stream into the streets to document agents. In the suburbs, the response looks different: it’s more spread out, and in some places, more politically difficult.

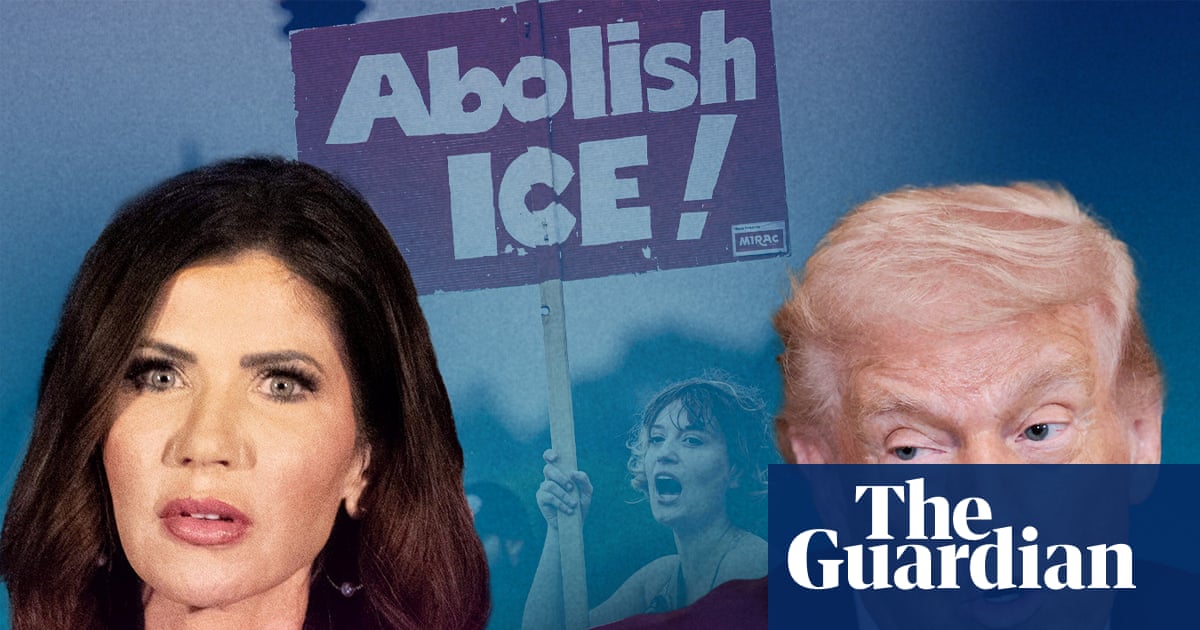

Tom Homan, Donald Trump’s “border czar”, announced on Thursday that the federal surge in Minnesota would be ending, with agents being drawn down over the course of this week and next. But they will leave a trail of havoc throughout the state, and it’s unclear when people will feel comfortable resuming normal activities. The surge of immigration agents into Minnesota has left no part of the state unscathed.

Joe Atkins, a commissioner in Dakota county, south-east of Minneapolis, said people often dismiss the impact of ICE as something happening in Minneapolis that won’t affect them, he said.

“But it’s happening here,” he said last month. “And there’s no denying it. We see it.”

In Minneapolis, the density of the city itself means that agents can quickly be outnumbered by observers on the streets. In suburban areas, rapid response covers larger geographic areas, and often people aren’t able to make it to a reported site of ICE activity until after agents have left.

Depending on the political makeup of an area, there are added dynamics at play: some in the community may agree with what ICE is doing, so those who are working to support immigrants must do so underground. Local governments may be helping behind the scenes but are not able to publicly make statements highlighting that work.

“In Minneapolis, it’s a little easier because you know most of the city supports you,” said the co-founder of an immigrant-led organization in an outer suburb, who asked that they and their organization not be identified due to fear of retribution and out of safety concerns. In other places, it is not as clear who is on your side, they said.

The organization is currently closed to the public, and its doors are locked. It offers services only by appointment and has removed its contact information from online services. It takes donations through third parties. The co-founder has been in hiding and keeps their child away from the community for safety reasons. They work with local elected officials, but those officials often don’t say anything publicly.

“We’re doing everything we can, but unfortunately, everything has to be done under the radar. Everything has to be done underground, because we don’t know who’s friendly and who’s not.”

Nicole Helget, who lives in Nicollet county, a rural region in southern Minnesota, said politically mixed areas have struggled to come to the same understanding of how to address the mass arrests.

“Some of the things communities need to do is try to get their leaders, their municipalities, into a shared reality, because sometimes that’s not even happening, and it’s difficult to move forward when the people making decisions don’t share a reality,” she said.

In Fridley, a suburb north of Minneapolis, the superintendent of the school district, Brenda Lewis, rides along with a school security employee each day. On a recent morning, Lewis encountered agents multiple times near an elementary school. The next day, it was quiet. It’s a familiar pattern: people across the metro reported a day or two of heavy federal presence, followed by an eerie calm once observers and patrols were alerted.

“Our district is heavy hit,” Lewis said. “We’re 80% students of color, we’re heavy east African, we’re heavy Hispanic, Latino. It has literally ended any sense of safety for our children and our families and our staff.”

Each school now has a dedicated security staffer at the doors and Lewis’s job has been consumed with responding to needs around the ICE surge. After she spoke out publicly, she has been followed by agents herself, as have members of the school board. The day of heavy activity came after she had spoken at a governor’s press conference and the district filed a lawsuit against the federal government over activity in or near schools.

“It’s become normalized now to see masked men with huge weapons in unmarked vehicles,” she said. “Five-year-olds should not be able to recognize ICE agents.”

Across the metro area, in early December, Pastor Miguel Aviles started ramping up food deliveries to people in the community around La Viña church in Burnsville, an outer suburb with a diverse population. In the two months since then, he has served thousands of families and signed up thousands of volunteers, some who have flown in to help.

On a recent afternoon, volunteers walked up to the stacks of food and supplies, filling boxes with produce, meat, eggs, bread and dry goods, which then are delivered by other volunteers to families in need.

Aviles is also now raising funds for rent, as many in the community aren’t sure how to pay bills after staying home for two months out of fear of ICE.

His community has been hit hard. Sunday services, usually attended by about 300 parishioners, now usually don’t get half that. One man, who had legal status, went out to deliver food with his two sons and was taken by agents, and the two boys returned devastated, Aviles said. The man was detained for almost three weeks before being released. Multiple families who attended the church decided to leave the state and return to their home countries, he said.

“This is the kind of story that will never appear in popular news headlines, yet it is the reality many of us have been living here – quiet, painful goodbyes that happen far from cameras and microphones,” he wrote on Facebook about those departures.

Erin Maye Quade, a Democratic state senator from Apple Valley, said thousands of people are involved in the rapid response groups in her area, forming safety teams at schools and daycares and mutual aid networks.

In January, she described agents stationed near gas stations, waiting to ask people for their paperwork. At any given time, she said, there are more immigration agents than local police in Apple Valley.

“The best way to describe it is that it is everywhere at any given time,” she said. “I think folks might have the impression that if you are just going about your life and you’re not participating in commuting or observing or doing something like a protest, that this doesn’t come across you. But you could be sitting in line to get Burger King and watch ICE snatch a worker on the way into work, you could be driving down the road and see an abandoned car, or have a swarm of cars come past you and then swarm a car.”

Nadia Mohamed, the mayor of St Louis Park, an inner suburb on the west side of the metro area, said her mother, who is a US citizen, will only leave the house if Mohamed is escorting her. Agents have been spotted throughout the city, including an incident in January when they were outside an elementary school.

Mohamed, the first Somali American to be elected mayor of a US city, said she is new to her neighborhood, and the first time she met some neighbors was when they would drop off food or leave notes for her during this time.

“That definitely subdues whatever anxiety and fear I may have,” she said.

Brad Tabke, a Democratic representative from Shakopee, said his district has been a “very intense” target of agents. In mid-January, he said there were days he would drive down the street and “this is not hyperbole, every other vehicle would be ICE”.

Matt Little, a Democrat who is running for Congress, said activity is different in each suburb – sometimes agents are at construction sites, or near schools or going around apartment buildings.

Videos posted on social media show Little knocking on agents’ car windows or asking them questions. It’s “definitely risky”, he said. Once, when he was going to a protest in Minneapolis, his six-year-old daughter grabbed snowboarding goggles and told him to wear them so agents couldn’t spray his eyes.

Still, he said, he can’t fathom staying home. “I have to be out there doing whatever I can. And if that means knocking on the door and talking to them, that’s what I’m gonna do.”

Atkins, the Dakota county commissioner, described schools with five times higher than normal absenteeism because of fear. He admits that when he first heard that ICE planned to come to Minnesota and target the “worst of the worst”, it sounded appealing. But what’s happening on the ground hasn’t looked like that at all. He spoke to a group of Republicans in January and most of them said that this is not what they signed up for. People who are largely apolitical or don’t follow politics closely are newly engaged.

“You expect them to be arresting the murderers and the pedophiles, and it’s been the gardeners and the housekeepers and the roofers and the construction guys and the adopted kid from Guatemala who’s been here for 30 years and was pulled over in the Aldi parking lot,” he said.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  3 weeks ago

3 weeks ago

Comments