UnitedHealth Group, the nation’s largest healthcare conglomerate, has secretly paid nursing homes thousands in bonuses to help slash hospital transfers for ailing residents – part of a series of cost-cutting tactics that has saved the company millions, but at times risked residents’ health, a Guardian investigation has found.

Those secret bonuses have been paid out as part of a UnitedHealth program that stations the company’s own medical teams in nursing homes and pushes them to cut care expenses for residents covered by the insurance giant.

In several cases identified by the Guardian, nursing home residents who needed immediate hospital care under the program failed to receive it, after interventions from UnitedHealth staffers. At least one lived with permanent brain damage following his delayed transfer, according to a confidential nursing home incident log, recordings and photo evidence.

“No one is truly investigating when a patient suffers harm. Absolutely no one,” said one current UnitedHealth nurse practitioner who recently filed a congressional complaint about the nursing home program. “These incidents are hidden, downplayed and minimized. The sense is: ‘Well, they’re medically frail, and no one lives for ever.’”

The Guardian’s investigation is based on thousands of confidential corporate and patient records obtained through sources, public records requests and court files, interviews with more than 20 current and former UnitedHealth and nursing home employees, and two whistleblower declarations submitted to Congress this month through the nonprofit legal group Whistleblower Aid.

The documents and sources provide a never-before-seen window into the company’s successful effort to insert itself into the day-to-day operations of nearly 2,000 nursing homes in small towns and urban commercial strips across the nation – an approach which has helped UnitedHealth secure a massive stream of federal dollars from Medicare Advantage plans that cover more than 55,000 long-term nursing home residents.

UnitedHealth said the suggestion that its employees have prevented hospital transfers “is verifiably false”. It said its bonus payments to nursing homes help prevent unnecessary hospitalizations that are costly and dangerous to patients and that its partnerships with nursing homes improve health outcomes.

Under Medicare Advantage, insurers collect lump sums from the federal government to cover seniors’ care. But the less insurers spend on care, the more they have for potential profit – an opportunity that UnitedHealth higher-ups have systematically sought to exploit when it comes to long-term nursing home residents.

To reduce residents’ hospital visits, UnitedHealth has offered nursing homes an array of financial sweeteners that sounded more like they came from stockbrokers than medical professionals.

Over the past seven years, the company has shelled out “Premium Dividend” and “Shared Savings” payments that boosted nursing homes’ bottom lines. Through its “Quality and Shared Risk” program, UnitedHealth offered an even bigger cut to nursing homes that drove down medical spending, but threatened to claw back money from those that didn’t, according to former employees and internal corporate documents.

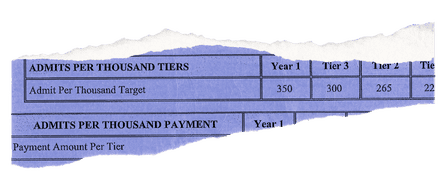

One term that UnitedHealth executives obsessed over was “admits per thousand” – APK for short. It was a measure of the rate that nursing homes sent their residents to the hospital. Under the “Premium Dividend” program, a low APK qualified a nursing home for the various bonus payments the insurer offered. A high APK meant that a nursing home received nothing.

“APK drove everything,” said one former national UnitedHealth executive who worked on the initiative with nursing homes in more than two dozen states and spoke about the confidential contracts on the condition of anonymity. “You gain profitability by denying care, and when profitability suffers for the shareholders, that’s when people get crazy and do things that are not appropriate.”

The revelations come at a time of crisis for UnitedHealth, which became the subject of public outrage after December’s fatal shooting of Brian Thompson, a top executive at the company, and the arrest of a suspect named Luigi Mangione.

The killing reignited concerns over the healthcare giant’s Medicare windfalls and denials of care to patients. But a full accounting of UnitedHealth’s cost-cutting push inside nursing homes has not previously surfaced amid government and media investigations into the company’s conduct.

Cost-cutting tactics

The secret bonuses were just one of many maneuvers UnitedHealth devised to track and cut expenses in its nursing home initiative.

Internal emails show, for example, that UnitedHealth supervisors gave their teams “budgets” showing how many hospital admissions they had “left” to use up on nursing homes patients.

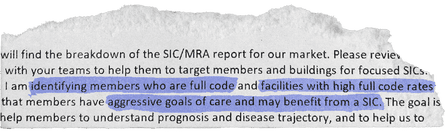

The company also monitored nursing homes that had smaller numbers of patients with “do not resuscitate” – or DNR – and “do not intubate” orders in their files. Without such orders, patients are in line for certain life-saving treatments that might lead to costly hospital stays.

Two current and three former UnitedHealth nurse practitioners told the Guardian that UnitedHealth managers pressed nurse practitioners to persuade Medicare Advantage members to change their “code status” to DNR even when patients had clearly expressed a desire that all available treatments be used to keep them alive.

“They’re pretending to make it look like it’s in the best interest of the member,” another current UnitedHealth nurse practitioner said. “But it’s really not.”

In response to questions, UnitedHealth said its nursing home initiative improves care for older residents by providing “on-site nurse practitioners, tailored care plans for chronic conditions, and enhanced communication between staff, families and providers”.

The company denied that it has prevented hospital transfers or inappropriately pushed patients to change their code status to DNR.

The program’s cost-cutting schemes were only possible because of the sprawling nature of UnitedHealth, a $300bn-plus conglomerate which has grown into one of the world’s biggest companies thanks to its relentless efforts to embed itself into nearly every corner of the healthcare industry. UnitedHealth’s insurance arm covers millions more Medicare Advantage seniors than any of its rivals, and another subsidiary, Optum, employs or affiliates with tens of thousands of doctors and nurse practitioners.

When nursing homes under the bonus program allowed medical teams from one UnitedHealth subsidiary to work in their facilities, they allowed the corporate giant to influence critical healthcare decisions for residents, which had a direct impact on the insurance side of its business.

The Guardian’s reporting also found that the program offered nursing homes even larger sums for every senior enrolled in the insurer’s offerings for long-term nursing home residents, which are called “Institutional Special Needs Plans”. In some cases, these payments incentivized nursing homes to leak confidential resident records to UnitedHealth sales teams so they could directly solicit elderly residents and their families, according to a whistleblower lawsuit currently being fought in federal court in Georgia as well as internal nursing home records and interviews with more than a dozen current and former nursing home employees and UnitedHealth salespeople.

One former UnitedHealth employee in Georgia admitted to the Guardian that she got nursing home staff to leak her confidential resident records then backdated permission-to-contact forms to circumvent federal rules meant to protect seniors from aggressive sales pitches. The employee was fired after failing to meet her sales quota, according to a former colleague.

After one nursing home near Savannah, Georgia, disclosed confidential patient records to UnitedHealth, families complained that their loved ones had been shifted onto the company’s Medicare Advantage plan even though they lacked the cognitive ability to make such decisions, according to a former UnitedHealth executive, federal court filings in Georgia and leaked patient files reviewed by the Guardian.

All told, the various payments that came with increasing UnitedHealth enrollments and minimizing medical expenses could add up to hundreds of thousands of dollars annually for a typical midsize nursing home, sources said.

But the nursing home residents, who had signed up for UnitedHealth’s Medicare Advantage program and whose federal dollars were financing the program, did not know about the confidential incentive payments and anti-hospitalization tactics affecting their care.

UnitedHealth declined to answer questions about how much it has paid out to nursing homes through the secret contract clauses. The company said its payments incentivize high-quality outcomes for residents and reward efforts that lead to improved care.

Maxwell Ollivant, a former UnitedHealth nurse practitioner, filed a congressional declaration this month with help from Whistleblower Aid, asking the federal government to hold the healthcare giant accountable.

In an interview with the Guardian – his first-ever public comment on the nursing home initiative – Ollivant urged lawmakers to make sure that UnitedHealth is “not skimping out on care” and that patients are not “signing up for a service and not receiving the service when the time comes”.

Ollivant previously filed a lawsuit in federal court in Washington state accusing UnitedHealth of withholding necessary services to nursing home residents, making their requests for Medicare payments violations of the federal False Claims Act. In 2023, the nurse practitioner dropped the suit after the Department of Justice declined to intervene. His congressional declaration provides new details of his experience.

In a statement, UnitedHealth said Ollivant “lacks both the necessary data and expertise” to assess the effectiveness of its programs. “We stand firmly behind the integrity of our programs, which consistently receive high satisfaction ratings from our members,” it said.

Dubious diagnoses, delayed hospitalizations

UnitedHealth pitches its nursing home initiative as a positive for long-term residents. It provides them access to UnitedHealth nurse practitioners via in-person visits as well as to remote medical professionals who provide guidance to facility nurses at night and on weekends.

This “enhanced care coordination”, as the company puts it, is supposed to help reduce unnecessary hospitalizations, which are costly for UnitedHealth and can expose patients to additional complications.

In several cases identified by the Guardian, the company’s insertion of itself into nursing home emergency protocols helped delay or avert transfers for patients who could have benefited from immediate hospital care.

In one incident from 2019, a remote UnitedHealth medical provider working for the program received a report shortly after midnight about a nursing home resident in Renton, Washington, who was slurring her words and unable to move her arm – textbook stroke symptoms.

In stroke cases, every minute counts. When blood flow to the brain is blocked or interrupted, brain cells quickly die. The sooner patients get to the hospital, the better the chance doctors have to prevent long-term neurological damage.

In this case, the nurse at her nursing home reported to UnitedHealth that it looked like a stroke, according to an incident log. But instead of greenlighting an immediate hospitalization for a possible stroke, the remote UnitedHealth employee suggested the resident might be suffering from a less serious condition called a transient ischemic attack (TIA), a temporary loss of brain function caused by blood flow blockage.

The remote employee then advised the nurse to run a blood test and update the company again in four hours, confidential UnitedHealth records show.

The patient’s independent primary care doctor told the Guardian she was never informed of this failure to transfer her patient.

“I would have wanted them to contact me right away so that I could have made a decision,” she said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive patient matters. “The timeframe matters.”

The independent doctor also said she was disturbed by the remote UnitedHealth employee’s working diagnosis, which called for ruling out a TIA, rather than a stroke. The remote employee was an early-career nurse practitioner, not a physician.

“Their diagnosis says TIA, [but] nobody can say that so early,” the patient’s doctor said.

In another incident that year, a nursing home nurse in Puyallup, Washington, delayed hospitalizing a resident also exhibiting potential stroke symptoms because of UnitedHealth protocols that pushed facility staff to wait for guidance from the company.

According to confidential nursing home records obtained by the Guardian, the nurse phoned a remote UnitedHealth provider, who was unsure about what to do and failed to call for an immediate transfer. Tired of waiting for a callback, the nurse finally bypassed the remote provider and called an independent doctor, who ordered the patient to be transferred.

But the delay meant that about an hour passed before the resident was actually taken to the hospital, which was only a few minutes away from his facility.

After the belated hospitalization, the patient suffered permanent verbal slurring and facial droop on the right side of his face, audio recordings and photos obtained by the Guardian show.

Citing confidentiality rules, UnitedHealth declined to comment on the specific patient cases. But the company noted that it does not prevent nursing homes themselves from contacting residents’ independent doctors, and that hospitalization decisions can depend on many factors including a patient’s goals of care, symptoms and the input of their care team.

UnitedHealth’s pressure on nursing home staff

UnitedHealth denied that its employees prevented hospital transfers and said it is the responsibility of the treating physician and the facility to decide on a patient’s best course of care.

But in practice, the company’s tactics put pressure on facility nurses to turn over patient care decisions to UnitedHealth staffers, according to internal documents and interviews with current and former UnitedHealth medical providers.

“There was never any caveat, given, like ‘It’s up to you all,’” said one former UnitedHealth doctor involved in the program. Nurses at the long-term care facilities “were calling the nurse practitioner or on-call provider who was responsible. The implication was that they were calling for advice that was meant to be followed.”

“A lot of times the nurses want to send people out and we have to go in and try to stop it,” said another current UnitedHealth nurse practitioner, who also spoke to the Guardian anonymously citing fears of retaliation. “And if we don’t, it’s on us. They take us out onto the carpet.”

In one patient case identified by the Guardian, nursing home staff sent a resident to the hospital because she was found unresponsive, drooling and with a “slant to the side” – possible stroke symptoms. She was admitted to the intensive care unit for a brain bleed, according to a UnitedHealth email reviewed by the Guardian.

But after the incident, instead of praising the facility team for the prompt hospitalization, a UnitedHealth manager alerted her subordinates that the facility team had bypassed the company’s protocol, failing to contact UnitedHealth’s remote on-call team first to receive guidance.

The manager met with the nursing home’s director of nursing services, and scheduled training to re-educate the facility’s nurses, the email shows.

UnitedHealth notes that unnecessary hospitalizations can expose patients to pressure injuries, falls and other complications. In response to questions from the Guardian, UnitedHealth pointed to one 2019 study which heralded the program’s success in reducing hospitalizations and noted the potential harms of hospital care.

But in an interview with the Guardian, Ollivant, the former UnitedHealth nurse practitioner turned whistleblower, argued such analyses fail to account for the negative health outcomes that patients suffer from missing hospital care.

“How many of those people were further harmed because they never received the care that they needed?” he said. “When you just look at the percentage reductions in hospitalizations, it doesn’t say anything about patient outcomes.”

A plan of care, an ailing patient

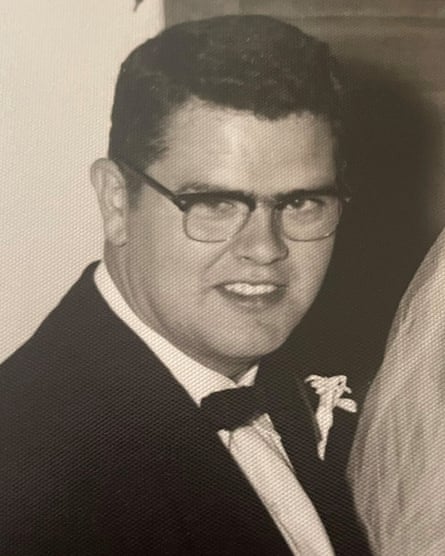

Kevin Keep never knew – until the Guardian called him last month and told him – that his father had suffered a possible stroke at a nursing home that partnered with UnitedHealth.

On the evening of 23 February 2019, a UnitedHealth remote employee received a report about Keep’s father, Donald Keep, a retired auto mechanic with dementia and an amputated leg living at a nursing home in Bremerton, Washington.

On that day, Keep was experiencing forgetfulness and drooping on the right side of his face – “possible stroke symptoms”, according to a confidential UnitedHealth incident log.

But instead of sending the octogenarian straight to the hospital, the remote employee referred to a plan of care that called for bloodwork and giving Keep an aspirin – a course of action which one former UnitedHealth doctor said “doesn’t make sense”, given the risk of brain damage.

“That’s not useful when it might be a stroke,” said the doctor, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to comment on Keep’s confidential patient records that he reviewed at the request of the Guardian. “What they really need is a physical exam and an MRI of the brain, and it needs to be done expeditiously.”

The incident log, which doesn’t mention a hospital transfer, suggests that the UnitedHealth team didn’t treat the case with the urgency that a possible stroke would require.

Keep’s symptoms were logged shortly before 10pm on a Saturday night. The next afternoon, a UnitedHealth employee emailed the company’s nurse practitioners a follow up note to look into what was wrong with Keep.

The email lists the proposed work-up as being for a “TIA” – the transient, less serious neurological condition, not a stroke.

As of 4pm on that Sunday, more than 18 hours after Keep was found with his face drooping, the work-up was still listed as “pending”.

Citing patient confidentiality, UnitedHealth did not respond to an inquiry about whether the retiree was ever sent to the hospital.

-

Hannah Recht contributed data reporting

-

Tomorrow, part two of UnitedHealth investigation: A tale of three whistleblowers

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  3 weeks ago

3 weeks ago

Comments