June Aochi Berk, now 92 years old, remembers the trepidation and fear she felt 80 years ago on Jan. 2, 1945. On that date, Berk and her family members were released by military order from the U.S. government detention facility in Rohwer, Arkansas, where they had been imprisoned for three years because of their Japanese heritage.

“We didn’t celebrate the end of our incarceration, because we were more concerned about our future. Since we had lost everything, we didn’t know what would become of us,” Berk recalls.

The Aochis were among the nearly 126,000 people of Japanese ancestry who had been forcibly removed from their West Coast homes and held in desolate inland locations under Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Feb. 19, 1942.

Approximately 72,000, or two-thirds, of those incarcerated were, like Berk, American-born citizens. Their immigrant parents were legal aliens, precluded by law from becoming naturalized citizens. Roosevelt’s executive order and subsequent military orders excluding them from the West Coast were based on the presumption that people sharing the ethnic background of an enemy would be disloyal to the United States. The government rationalized their mass incarceration as a “military necessity,” without needing to bring charges against them individually.

In 1983 a bipartisan federal commission found that the government had no factual basis for that justification. It concluded that the incarceration resulted from “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

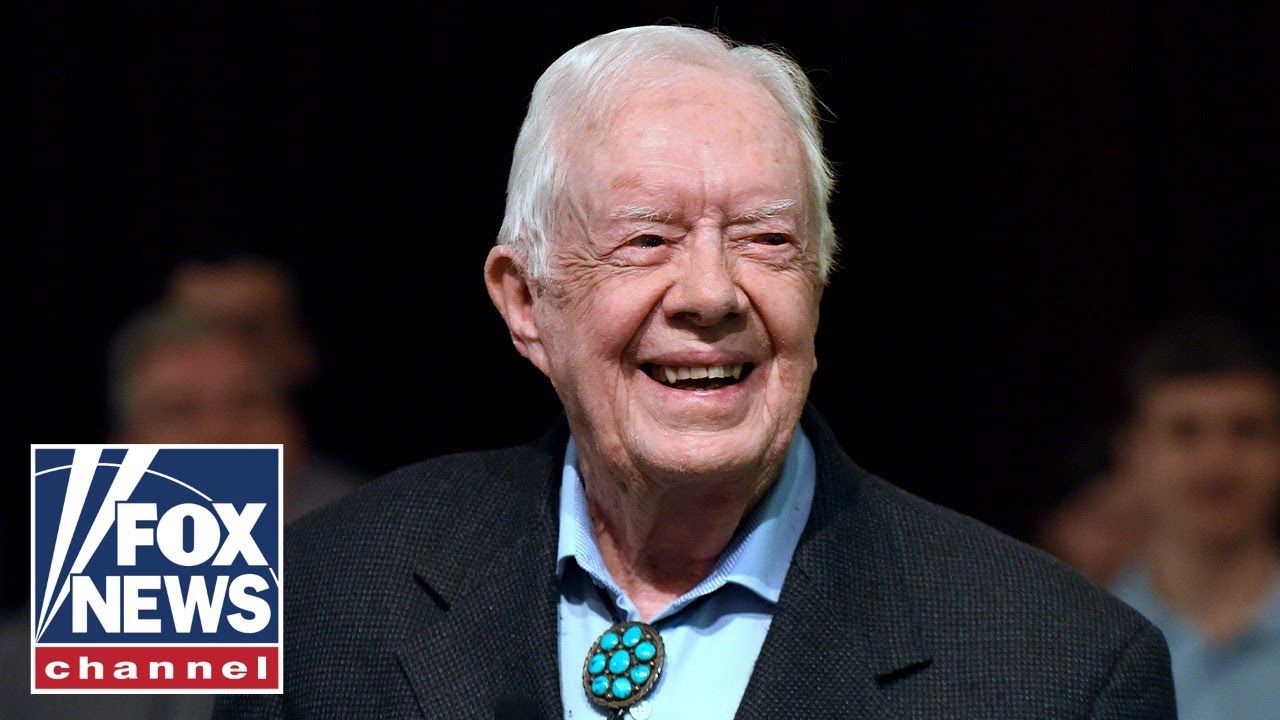

The commission recommendations resulted in the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. Signed by President Ronald Reagan, the law provided surviving incarcerees with an apology for the unjustified government actions and token $20,000 payments. This legislation and various judicial rulings have recognized that the incarceration was an egregious violation of U.S. constitutional principles, a race-based denial of due process.

No formal, comprehensive records

A key element of this tragic and disgraceful chapter of American history is that nobody ever kept track of all the people who had been subjected to the government’s wrongful actions.

To reckon with this injustice, the Irei Project: National Monument for the WWII Japanese American Incarceration was launched in 2019. This community nonprofit project was originally incubated at the University of Southern California Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture, with a goal to create the first-ever comprehensive list of the names of every individual incarcerated in America’s wartime internment and concentration camps.

Taking the project name “irei” from the Japanese phrase “to console the spirits of the dead,” the project was inspired by stone Buddhist monuments that the detainees built while incarcerated in Manzanar, California, and Camp Amache, Colorado, to memorialize those who had died while wrongfully detained.

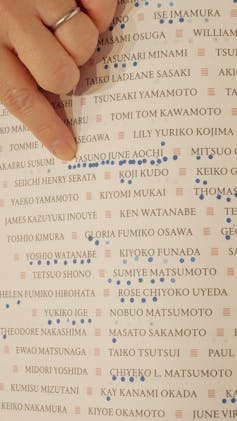

The phrase “approximately 120,000” incarcerees has often been used by scholars, journalists and the Japanese American community because the exact number of those incarcerated has never been known. By creating an actual list of names, the Irei Project has sought to confirm an accurate count and to restore dignity to each person who experienced some constitutional injustice when the U.S. government reduced them to faceless enemies.

With the goal of leaving no one out, a dozen part-time researchers on the Irei team searched records in the National Archives and in the collections of other government institutions. Working with Ancestry.com and FamilySearch, Irei researchers have developed innovative methodologies and protocols to verify identities, the places of detention and, importantly, the accurate spelling of names. More than 100 volunteers assembled and fact-checked the data.

As just one example of making sure the historical record is correct, a search through National Archive microfilm records revealed that “Baby Girl Osawa” was born to a mother incarcerated in the temporary detention facility known as the Pomona Assembly Center. Sadly, the baby lived only a few hours.

Leaving no one out means that this infant is now among the nearly 6,000 additional people that the Irei Project has documented as among those who were incarcerated. As of November 2024, the number is 125,761; as the research continues, the number of documented incarcerees will continue to grow.

The pain of enduring and remembering

Without any means to return to their prewar neighborhood in Hollywood, California, the Aochis went to Denver, Colorado, where friends offered to help them get back on their feet. They and the other incarcerees girded themselves to face prejudice and hostile treatment that had only intensified during the war, to the point of terrorism.

“After the war, we just had to concentrate on restarting our lives, and we had to put the trauma of the incarceration behind us,” Berk explained.

For Berk, her fellow incarcerees and their descendants, the Irei Project provides some acknowledgment of the loss of dignity suffered by individuals, families and communities.

“We were taught not to complain,” remembers Berk, “and yet it’s painful now to think about the endless ways in which we were mistreated. Do you know what it is like to be forced to live in a horse stable?”

In the years following their incarceration, survivors would often cite how each incarcerated family was rendered nameless when the government issued them a family number that supplanted their surname. Betty Matsuo, incarcerated at 16 and detained in the Stockton Assembly Center and Rohwer Relocation Center, told the congressional commission, “I lost my identity. At that time, I didn’t even have a Social Security number, but the (War Relocation Authority) gave me an ID number. That was my identification. I lost my privacy and my dignity.”

For others, suppressing their anger, frustration and shame at being treated like a criminal when they had not done anything wrong impaired their health and relationships. Mary Tsukamoto, incarcerated at 27 and detained in the Fresno Assembly Center and Jerome Relocation Center, felt powerless after the war as the government actions were continuously held up as justified, even though there was never any factual basis for suspecting the Japanese American community of wholesale disloyalty. In 1986, she testified before a congressional committee that for decades “we have lived within the shadows of this humiliating lie.” Tsukamoto thought it was important to “gain back dignity as a people who can all dream of a (n)ation that truly upholds the promise of … (j)ustice for (a)ll.”

Healing and reconciliation

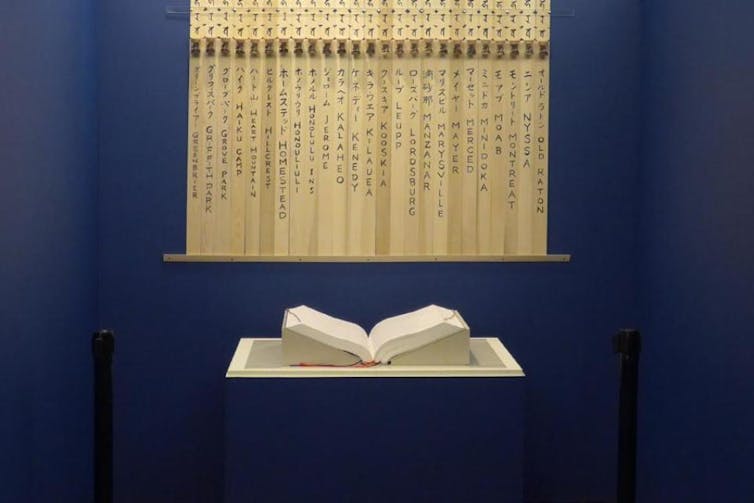

To see the names of those who were incarcerated in a ceremonial book called the Ireichō, which means “record of consoling spirits” in Japanese, is to recognize their suffering. The Ireichō has been on display for the past two years at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

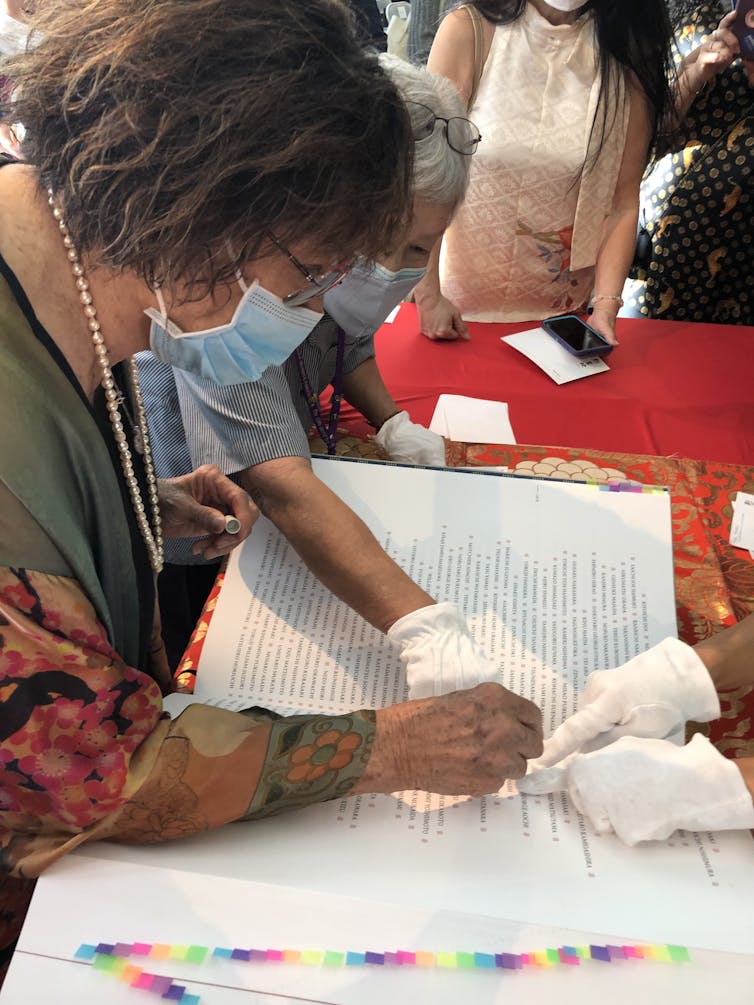

Any member of the public could make a reservation to place a blue dot stamp beneath the names, symbolically representing the Japanese tradition of leaving stones at memorial sites. Although anyone could stamp names without any relationship to an incarceree, many surviving incarcerees have assembled their descendants and friends together to stamp names of extended family members.

“The Ireichō has become an iterative form of a monument, drawing visitors as if they are pilgrims to a sacred site,” said Ann Burroughs, the museum’s president and CEO.

Berk was one of the first to stamp the book, choosing to honor her parents, Chujiro Aochi and Kei Aochi. “My parents set such a resilient example, and by paying this tribute to them, I am able to do something positive to help overcome all of the difficult memories,” Berk explained. For the community, each stamp is a small but meaningful act toward repairing the indignities suffered by each incarceree and reconciling with the past.

Plans are for the Ireichō to go on a national tour, with the goal of having each name stamped at least once. Other components of the Irei Project include the Ireizo, an interactive and searchable online archive, and the Ireihi, light sculptures slated to be placed at eight former World War II confinement sites starting in 2026.

On Dec. 1, 2024, Berk gathered her five children and eight grandchildren with their partners to stamp her name and to place additional stamps by the names of her parents. She said, “My children and grandchildren have a better understanding now of what happened to us during the war. This is a time of history we should never forget, lest our government ever takes such actions again and inflicts this painful experience upon any other person or group.”

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  2 days ago

2 days ago

Comments