When Abigail Leonard saw the news that the Trump administration was considering handing out $5,000 “baby bonuses” to new mothers, she realized that she had already received one.

A longtime international reporter, Leonard gave birth to three children while living in Japan, which offers a year of parental leave, publicly run daycare, and lump-sum grants to new parents that amount to thousands of US dollars. But it was not until moving back to the US in 2023 that Leonard grasped just how robust Japan’s social safety net for families is – and, in comparison, just how paltry the US net feels.

Not only is the US the only rich country on the planet without any form of national paid leave, but an uncomplicated birth covered by private insurance tends to cost families about $3,000, which, Leonard discovered, is far more than in most other nations. The federal government also spends a fraction of what most other wealthy countries spend on early education and childcare, as federally subsidized childcare is primarily available only to the lowest earners. Middle-class families are iced out.

Leonard traces the effects of policies and disparities like these in her new book, Four Mothers, which follows the pregnancy and early childrearing experiences of four urban, middle-class women living in Japan, Kenya, Finland and the US. Published earlier this month, Four Mothers provides a deeply personal window into how policy shapes parents’ lives. And it has emerged as an increasingly rightwing US seems poised to embrace the ideology of pronatalism and policies aimed at convincing people to have more kids.

Pronatalism is deeply controversial, in no small part because its critics say pronatalists are more concerned with pushing women to have kids than with ensuring women have the support required to raise them.

“Being ‘pronatal’ – designing policy to increase the birthrate – is not the same thing as being pro-woman,” Leonard notes in Four Mothers’ introduction. A $5,000 check would not have been enough to help any of the moms profiled in the book. Instead, the women relied on – or longed for, in the case of the US – extensive external support, such as affordable maternity care, parental leave and access to childcare.

“The book is an implicit comparison of the rest of the world to the US, and parenthood is so much harder here in many ways,” Leonard said in a phone interview with the Guardian. “People are so accepting that things can be privatized and that government can be torn down and that there won’t be any repercussions to that. We don’t think about how integral government policy is to our lives, and for that reason can’t imagine how much more beneficial it could be.”

In the US, resistance to increasing government aid in childrearing has long gone hand in hand with a commitment to upholding a white, traditional view of the American family. At virtually every juncture, rightwing groups have been galvanized to stop sporadic efforts at expanding support. During the second world war, Congress allocated $20m to a universal childcare program that could help women work while men fought in the war effort. The program was so popular that people protested in the streets to keep it even after the war ended, according to Leonard. But the program was dismantled after political disputes over how to run the program, as southern states demanded that the daycares be segregated.

In 1971, Congress passed the Comprehensive Child Development Act, which would have created a national system of federally subsidized daycare centers. Inflamed by the idea that the bill would encouraged women to work outside the home, church groups organized letter-writing campaigns against the bill. Rightwing pundits, meanwhile, claimed the bill was “a plan to Sovietize our youth”. Richard Nixon ultimately vetoed the bill, calling it “the most radical piece of legislation” to ever cross his desk.

Today, Leonard writes, corporations have an entrenched interest in keeping childcare from becoming a public good in the US. Private equity is heavily invested in childcare companies. Wealthy corporations, especially big tech companies, can also use their generous paid leave policies to lure in the best talent.

“I talked to a congressman who was telling me he was trying to get some of these companies on board to back a national paid leave policy, and they were saying: ‘We don’t want to do paid leave because then we give up our own competitive advantage.’ It’s so cynical,” Leonard said. “These are companies that have been able to create this image around themselves of being feminist and pro-family. Like: ‘They’re great places to work for women. They help fund fertility treatments!’”

She continued: “They’ve feminist-washed themselves. They’re working against a national policy that would benefit everyone and that ultimately would benefit our democracy, because you wouldn’t have this huge inequality of benefits and lifestyles.”

‘A grind’

The US has become far more accepting of women’s careerist ambitions over the last 50 years – especially as it has become more difficult for US families to sustain themselves on a single income – but balancing work and family life is still often treated as a matter of personal responsibility (or, frequently, as a personal failing).

To improve mothers’ lives, Leonard found, a commitment to flexible gender norms – in the home and at work – must be coupled with a robust social safety net.

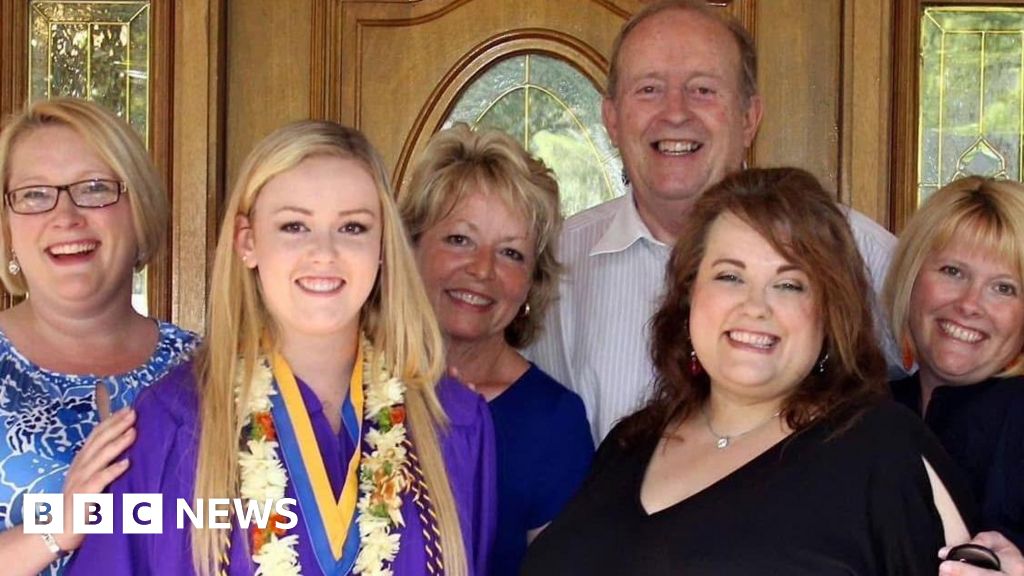

Each of the women in Four Mothers struggled with male partners who, in various ways and for assorted reasons, failed to provide as much childcare as the mothers. Sarah, a teacher in Utah, was married to an Amazon delivery driver who got zero parental leave. Sarah was entitled to three months of leave, at partial pay, but only because her union advocated for it. Although Sarah and her husband chose to leave the Mormon church, she found herself longing for the community that the church provided because it offered some form of support and acknowledgement of motherhood.

Finland perhaps fares the best in Leonard’s book. The country, which gives parents about a year of paid leave, invests heavily in its maternal care system and has some of the lowest infant and maternal mortality rates in the world; it even offers mothers prenatal counseling where they can discuss their own childhoods and how to break cycles of intergenerational trauma. (The US, by contrast, has the highest maternal mortality rate of any wealthy country.) Finland is also the only industrialized nation on the planet where fathers spend more time with their children than mothers do. (The difference is about eight minutes, “about as even as it can be”, Leonard wrote in Four Mothers.) Parents are also happier than non-parents in Finland – which is routinely ranked as the happiest country in the world – while the inverse is true in the US.

Still, the birth rate is on the decline in Finland, just as it is in Japan and the US. It is not clear what kinds of pronatalist policies, if any, induce people to have kids. Nearly 60% of Americans under 50 who say they’re unlikely to have children say that’s because “they just don’t want to”.

“The pronatal argument here – that’s really focused on people who make the choice not to have children. That is not only cruel and mean, but it’s also ineffective, because people who don’t want to have kids probably aren’t going to have kids and none of this stuff is going to make a difference,” Leonard said.

That said, had she been building her family in the US rather than Japan, Leonard doesn’t know if she would have had three children. Given the cost of US childcare, “it would have been more of a grind”.

“I just think it’s harder and more expensive here. So it was somewhat easier to have that third child there,” Leonard said. “It’s not because they gave me a $5,000 baby bonus.”

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  1 day ago

1 day ago

Comments