The last four years’ stunning rebound from the pandemic wasn’t enough to keep a Democrat in the White House. Now Donald Trump is moving back in with many economic winds at his back and a pocketbook-focused electorate watching to see what he’ll do with them.

The economy the president-elect inherits isn’t perfect, but he has eagerly positioned himself as the solution to its flaws.

Unavoidable expenses like housing, child care, health care and more remain punishingly high for countless households, whose frustrations Trump successfully channeled during the campaign — when he hosted rallies under enormous “Trump will fix it!” signs. He has promised to slash energy costs in half within his first year and free up more housing by ejecting millions of immigrants from the country.

However, the costs of many daily goods and services have already slowed sharply while workers’ incomes, on average, have more than made up for the hikes. Since inflation peaked in June 2022 at 9.1%, the annual pace of consumer price increases is now less than 3%, where it has hovered for months just above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target rate.

But December’s 2.9% reading is the latest sign that the last mile of the inflation road can be bumpy.

Price increases have accelerated in the Biden administration’s final months after having touched 2.4% in September, the lowest level since February 2021. Food costs have risen every month since August, stalling after dramatic improvement earlier last year. Indeed, having relentlessly highlighted grocery prices on the stump, Trump said after the election that bringing them down further would be “very hard.”

Food costs have risen every month since August, stalling after dramatic improvement earlier last year.

A surge in energy prices fueled 40% of inflation’s gains last month, though they’re still a bit cheaper than a year ago. The uptick was driven mainly by gasoline and fuel oil in a season when utility bills are expected to jump nearly 9% from steeper home heating costs.

It’s ironic, meanwhile, that efforts to lower inflation could be hampered by the underlying strength in the labor market and the economy overall.

Looking to cement its record, the Biden administration released a Treasury Department analysis last week emphasizing that “labor market, household, and business indicators are all at levels typical of economic booms, with some — including the prime-age (ages 25 to 54) labor force participation rate, median household wealth, and business applications — at or near historic highs.”

Monetary policymakers at the Fed, who are doubtless watching those measures closely, have historically trimmed interest rates to goose a flagging economy. But with things broadly humming along, they’re keenly aware that goosing it too soon, or by too much, could undo hard-won progress and send prices higher again.

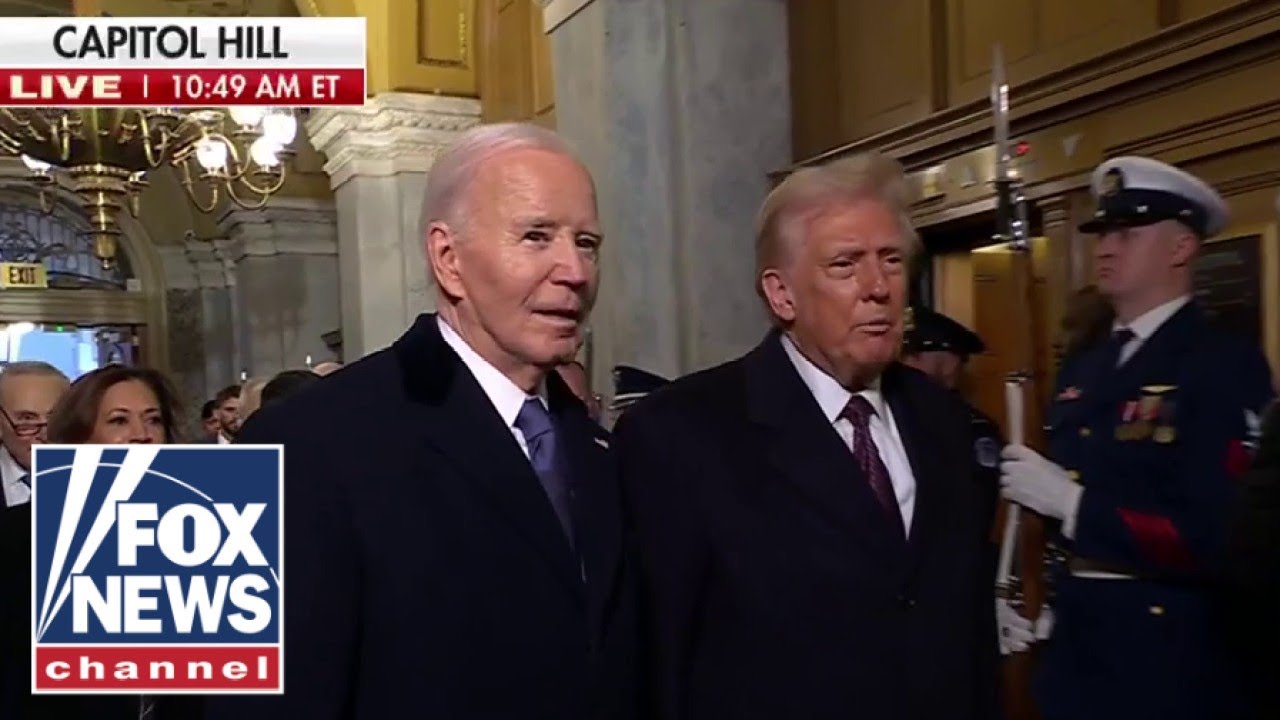

What happens next also depends on the policies Trump implements shortly after he takes the oath of office for a second time.

He has indicated his tax and immigration crackdown proposals are top priorities. Business executives are eager for the former, especially plans to pair a lower corporate tax rate with deregulation. Economists say Trump’s vow to detain and deport millions of undocumented people could send tremors through major industries that rely heavily on immigrant laborers, especially agriculture, health care and construction.

Authorities processed migrants in California last summer. Trump has made cracking down on immigration key to his economic agenda.

Trump’s tariff plans are another wild card that threatens to ratchet up diplomatic tensions with allies and rivals alike and raise costs for businesses from tech startups to craft breweries and bicycle makers. Given such unknowns, market experts are dialing back expectations for the pace of further interest rate cuts by the Fed.

“We believe the resiliency of the U.S. labor market, stickiness in inflation and uncertainty emanating from federal economic policy will keep the FOMC on hold for the next several months,” Wells Fargo economists wrote recently in a note to clients, referring to the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee.

Economists at BNP Paribas even see the Fed on hold for the rest of the year. “We continue to expect no cuts in 2025 based on an inflationary upsurge from the new administration’s policies,” they wrote to clients. That would keep borrowing costs uncomfortably high for credit cards, car loans and a variety of other rates tied to the Fed’s benchmark. The yield on 10-year Treasury bonds, on which mortgage rates are based, has been rising, too.

And then there’s simply the national mood. Trump earned most voters’ trust to handle the economy better than his predecessor. But he’ll have his work cut out for him turning around a persistently sour outlook shared by millions of people, despite long-running partisan gaps on the matter.

“Inflation is improving, but most people don’t agree,” said Greg Valliere, chief U.S. policy strategist at AGF Investments. He added that there’s also the potential for conflict between Trump and Fed Chair Jerome Powell, whom Trump has said he won’t try to remove from atop the central bank before Powell’s term ends in May 2026.

“Trump undoubtedly thought he would get a few interest rate cuts in 2025, but he may not get any — or just one or two,” Valliere said. “He and Powell have a history of feuds, and that may re-erupt if the Fed refuses to cut rates.”

Still, context is critical. Inflation clocked in at 2.9% on average over last year as a whole, slower than 2023’s full-year rate of 3.3% and below the long-term average of 3.5%, according to Charles Schwab investment strategist Kevin Gordon.

That’s a favorable trend, but it can be difficult for people to see unfolding in the worlds where they live, work, shop and vote — or for politicians to continue after having swept into office promising change.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)

Comments