At a time when China is believed to spend about US$8 billion annually sending its ideas and culture around the world, President Donald Trump has proposed to cut by 93% the part of the State Department that does the same thing for the United States.

The division is called the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs. Among its other activities, the bureau brings foreign leaders to the U.S. for visits, funds much of the Fulbright international student, scholar and teacher exchange program and works to get American culture to places all across the globe.

Does this matter?

As a historian specializing in the role of communication in foreign policy, I think it does. Reputation is part of national security, and the U.S. has historically enhanced its reputation by building relationships through cultural tools.

Previous U.S. administrations have realized this, including during President Donald Trump’s first term, when his team, led by Assistant Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs Marie Royce, raised the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs budget to an all-time high.

Giving politics a human dimension

Government-funded cultural diplomacy is an old practice. In 1889, President Benjamin Harrison’s government hosted a delegation of leaders from Latin America on a 5,000-mile rail tour around the American heartland as a curtain raiser for the first Pan-American conference. The visitors met a variety of American icons, from wordsmith Mark Twain to gunsmiths Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson.

President Teddy Roosevelt initiated the first longer-term cultural exchange program by spending money raised from an indemnity imposed on the Chinese government for its mishandling of the Boxer Rebellion, during which Western diplomats had been held hostage. The program, for the education of Chinese people, included study in the U.S. In contrast, European powers did nothing special with their share of the money.

During World II, Nelson Rockefeller, who led a special federal agency created to build links to Latin America, brought South American writers to the U.S. to experience the country firsthand. In so doing, he invented the short-term leader visit as a type of exchange.

This work went into high gear during the 1950s. The U.S. sought to stitch postwar Germany back into the community of nations, so that nation became a particular focus. Programs linked emerging global leaders to Americans with similar interests: doctor to doctor; pastor to pastor; politician to politician.

I found that by 1963, one-third of the German federal parliament and two-thirds of the German Cabinet had been cultivated this way.

Visits gave a human dimension to political alignment, and returnees had the ability to speak to their countrymen and women with the authority of personal experience.

From jazz to promoting peace

The globally focused International Visitor Leadership Program built early-career relationships between U.S. citizens and young foreign leaders who later played a central role in aligning their nations with American policy.

Nearly 250,000 participants have traveled to the U.S. since 1940, including about 500 who went on to lead their own governments.

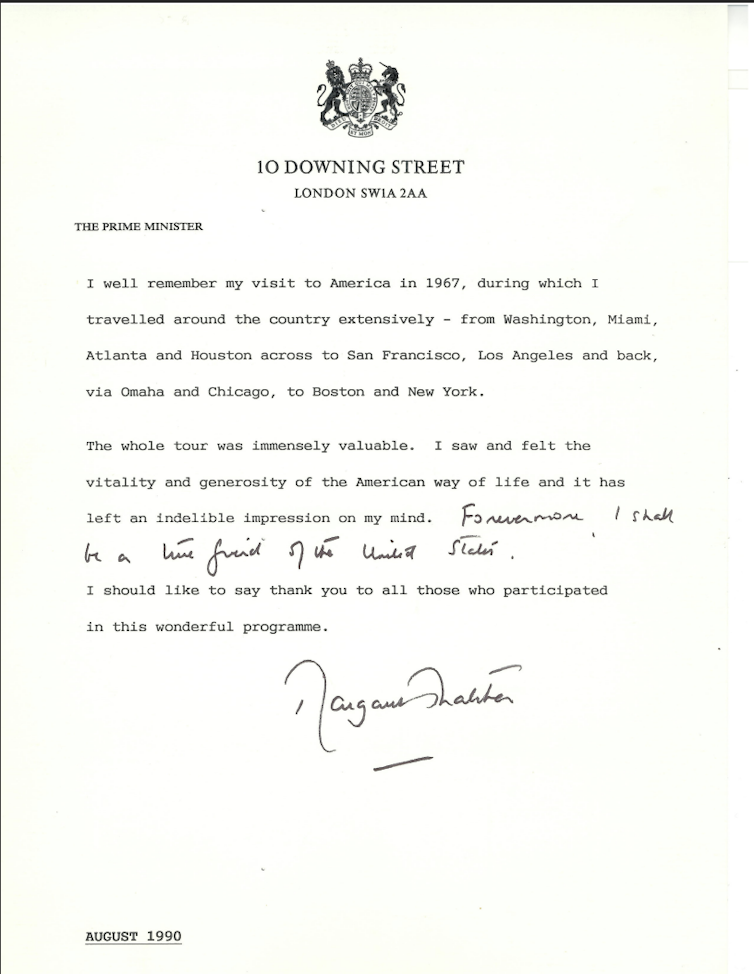

Future Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of Britain visited as a young member of Parliament; F.W. De Klerk came from South Africa and saw the post-Jim Crow South before he helped lead his country to dismantling apartheid; and Egypt’s Anwar Sadat visited the U.S. and began to build trust with Americans a decade before he became leader of his country and partnered with President Jimmy Carter to advance peace with Israel.

Cultural work more broadly has included helping export U.S. music to places where it would not normally be heard. The Cold War tours of American jazz musicians are justly famous. Work bringing together the world’s sometimes persecuted writers for creative sanctuary at the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa is less well known.

The Reagan administration arranged citizen-to-citizen meetings with the Soviet Union to thaw the Cold War. Reagan’s theory was that ordinary citizens could connect: He imagined a typical Ivan and Anya meeting a typical Jim and Sally and understanding each other.

Current programs include bringing emerging highfliers in tech, music and sports to the U.S. to connect to and be mentored by Americans in the same field and then go home to be part of a living network of enhanced understanding. Such programs are in danger of being cut under Trump.

Personal experience conquers stereotypes

How exactly does this work advance U.S. security?

I see these exchanges as the national equivalent to the advice given to a diplomat in kidnap training: Try to establish a rapport with your hostage-taker so that they will see the person and be inclined to mercy.

The Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs is the part of the Department of State that cultivates empathy and implicitly counters the claims of America’s detractors with personal experience. Quite simply, it is harder to hate people you really know. More than this, exchanged people frequently become the core of each embassy’s local network.

Of course, an exchange program is just one part of a nation’s reputational security.

Reputation flows from reality, and reality is demonstrated over time. Historically, America’s reputation has rested on the health of the country’s core institutions, including its legal system and higher education as well as its standard of living.

U.S. reputational security has also required reform.

In the 1950s, when President Dwight Eisenhower faced an onslaught of Soviet propaganda emphasizing racism and racial disparities within the U.S., he understood that an effective response required that the U.S. not only showcase Black achievement but also be less racist. Civil rights became a Cold War priority.

Today, when the U.S. has no shortage of international detractors, observers at home and abroad question whether the country remains a good example of democracy.

As lawmakers in Washington debate federal spending priorities, building relationships through cultural tools may not survive budget cuts. Historically, both sides of the political aisle have failed to appreciate the significance of investing in cultural relations.

In 2013, when still a general heading Central Command, Jim Mattis, later Trump’s secretary of defense, was blunt about what such lack of regard would mean. In 2013 he told Congress: ‘If you don’t fund the State Department fully, then I need to buy more ammunition, ultimately.“

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  1 day ago

1 day ago

Comments