The Trump administration has revived the practice of separating families in order to coerce immigrants and asylum seekers to leave the US, attorneys and former immigration officials allege.

In several cases, officials have retaliated against immigrants who challenged deportation orders by forcibly separating them from their children, a Guardian investigation found. The officials misclassified the children as “unaccompanied minors” before placing them in government-run shelters or foster care.

The new practice has taken effect as the administration has also issued stringent new limits on who can take custody of unaccompanied minors – which advocates say keep thousands of children away from their relatives.

“This is a tactic to punish people for not acquiescing,” said Faisal Al-Juburi, head of external affairs at the legal aid group Raíces. “It’s a tactic to get immigrants to relent, to agree to self-deport.”

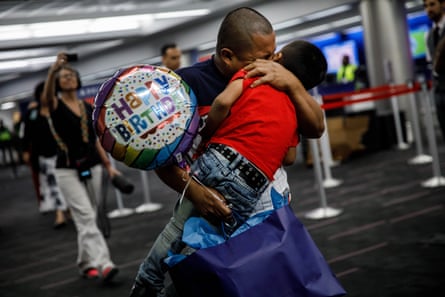

The recent separations echo the “zero tolerance” policy of the first Trump administration, when the US systematically separated more than 5,600 migrant children from their parents and caregivers at the US-Mexico border. Images of agents pulling children from their parents’ arms and placing them in overcrowded metal cages sparked domestic and international outrage, and Donald Trump ended the policy.

But seven years later, hundreds of parents have still been unable to reunify with their children; the administration lost track of many of the families it tore apart. Though the new separations so far appear less pervasive than the original policy, experts and attorneys said that it could result in another crisis of prolonged, permanent separations.

“I would say that the main difference is just that the separations are now happening all over the country, as opposed to at the border, concentrated in areas where you could visibly go see it,” said Michelle Brané, a former Department of Homeland Security (DHS) official who served under the Biden administration. “But the rest of it is not that different. The objective is still to be cruel and send a message that people should not come to the US – that they should leave.”

Family separation is one of several ways in which the US government is, increasingly, moving immigrants around the country – shuffling detainees through a vast, chaotic system that advocates say is intentionally cruel.

An analysis of leaked flight records and US government detention data, as well as interviews with immigrants, attorneys and former officials, revealed that immigrants are increasingly moved without notice away from their families, communities and legal counsel – leading to apparent violations of constitutional due-process rights.

The Guardian reviewed leaked flight data from Global Crossing Airlines, the charter company that operates the majority of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice) flights, and found that the vast majority of these trips during the first three months of the second Trump administration were between domestic US airports. The airline transported nearly 44,000 immigrants – including 1,000 children – during that time. US detention data revealed that since the inauguration, nearly 2,350 kids under the age of 18, including 36 infants, have been booked into immigration detention centers around the country.

In cases reviewed by the Guardian, parents were moved between detention centers several times after being separated from their children – and in the process were unable to coordinate calls with their kids or their lawyers. Amid the chaos, immigration experts and advocates have the raised alarm that the government could, as it did during the first Trump administration, lose track of where it is sending parents and children – resulting in indefinite or permanent separations.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) did not respond to the Guardian’s request for comment.

For LW, a 37-year-old mother who came to the US with her 10-year-old son in April seeking political asylum, returning to China was not an option.

LW told her lawyers and immigration officers that she had been sexually assaulted by multiple high-ranking government officials in China. After reporting an assault to the police, Chinese government operatives threatened her with imprisonment – or death. That’s what was awaiting her in China, she told US immigration agents.

In a sworn declaration in her immigration case that her lawyers shared with the Guardian, LW alleged her pleas to allow her and her son to remain together while they applied for asylum were ignored by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents in San Diego, California, who forced the mother and son into an unmarked vehicle, and began driving them toward the local airport. According to her sworn declaration, agents told her if she refused to get on a flight back home, the government would take her son away from her.

At the airport, the agents tried to drag LW toward the terminals. “I said I needed a lawyer, but they refused, telling me that nobody would want to help me,” she said in her declaration. “Desperate and terrified of what might happen, I dropped to the ground and the officers let me go.”

Later that day, she said they drove her and her son back to a CBP facility in San Diego – and then moved them to an Ice facility in Texas. But a month later, she said, immigration agents followed through on their threat: they took her son away and placed him in foster care.

Her lawyers said that she and her son have now been separated for nearly five months. He turned 11 in the interim.

LW remains detained at an Ice facility in New Mexico, while her son has been placed at a government shelter for unaccompanied minors in New York.

Her lawyers from Raíces have repeatedly petitioned for her release, arguing that her prolonged separation from her son was in violation of a court settlement that had blocked family separations during the first Trump administration. But Ice told LW’s lawyers that the settlement did not apply in this case. LW said agents told her she could be reunited with her son if she agreed to accept deportation to China.

The DHS has said it always gives parents a choice. “Rather than separate families, Ice asks parents if they want to be removed with their children or if the child should be placed with someone safe the parent designates,” Tricia McLaughlin, a spokesperson for the DHS, told the Guardian in September.

But in each of the cases reviewed by the Guardian, lawyers said their clients weren’t offered a real choice. In some instances, parents were not fully informed of their options prior to being separated from their children. In others, none of the available options were safe, or possible.

LW couldn’t choose to leave her son with another parent or guardian, her lawyers said. Though her boyfriend was already in the US and had offered to act as a legal sponsor, he wasn’t the boy’s biological father and it was unclear that he could fulfill the government’s steep requirements to take custody of him.

New policies the Trump administration enacted in January require that anyone seeking to take custody of unaccompanied minors in government-run shelters or foster care must provide proof of their income source, show a US identification and in many cases take a DNA test.

A federal lawsuit on behalf of several migrant youths and the legal aid groups representing them alleges that these new requirements have disqualified many parents, siblings and other family members from taking custody of children who have been classified as “unaccompanied minors”.

“We’re seeing separation being used as a punitive measure,” said Al-Juburi. “A punitive measure for not acquiescing, for demanding access to legal counsel, and for staking claim to her and her son’s rights to apply for asylum.”

As the Trump administration attempts to make good on the president’s campaign promise to enact mass deportations and expel 1 million people each year, legal aid groups and immigration experts say that it appears to be using the threat of separation as one of many aggressive strategies to speed up the removal of migrants from the country.

In Texas, which is home to Ice’s sole detention facility currently designated specifically for family units, Raíces has served approximately 250 families this year to date, according to Al-Juburi. Of these families, about 10% have endured some kind of separation while in Ice custody.

“This pattern is deeply troubling,” said Elora Mukherjee, a lawyer and the director of Columbia Law School’s Immigrants’ Rights Clinic, who has been advocating on behalf of several clients threatened with separation.

Among Mukherjee’s clients are a two-year-old and a seven-year-old. “An Ice officer has threatened to separate each of these children from each other and from their mother and their father, detain them in separate facilities, and put them on four different deportation flights,” she said. “This is unnecessarily cruel.”

Many of the migrant families threatened with separations have already made long, dangerous journeys to the US.

For Muhammad, a 24-year-old father of four, the journey out of Afghanistan included stopovers in Pakistan, Brazil (where his seven-year-old stepdaughter was kidnapped for ransom) and Mexico (where he had to pay a smuggler to help his family make their way across the US’s southern border).

Muhammad’s wife had worked in human rights prior to the US military’s withdrawal from Afghanistan in the summer of 2021. Once the Taliban took power, she began receiving death threats. Her father – a military general under the prior government – was killed, as was Muhammad’s uncle. The couple knew that they and their children had to leave.

They first fled to Pakistan, then got a temporary visa to Brazil. But after Muhammad’s seven-year-old stepdaughter was kidnapped and held for ransom there, he and his wife knew they couldn’t stay.

Finally – in February 2025, about a month after Trump was sworn in as president – they arrived at the US-Mexico border. By then, the Trump administration had shut down nearly all avenues to apply for asylum at the southern border, so Muhammad and his wife felt they had no choice but to pay a smuggler to bring them into the US, where they turned themselves over to immigration authorities.

“We have traveled far in search of safety,” said Muhammad, in a sworn declaration in his immigration case that was shared with his permission by his lawyers at Raíces. “I believe that the US is the safest place to raise my family and provide them with all that they deserve and need.”

But he hasn’t been able to hold them in nearly six months. His one-year-old, who was born in Brazil, has been growing up rapidly without him.

Initially, immigration officials detained the family together, at a CBP facility and then at a family detention center in Karnes, Texas. Then, on 31 March, Muhammad was told he would be escorted to the medical center for an evaluation. It was odd, because he hadn’t made an appointment or asked to see a doctor.

“I asked for a moment to say goodbye to my family, but the officer told me I would see them the following day, and not to worry,” Muhammad said. He was handcuffed and placed in a dark room. The next day, he said he was moved to a different detention center in Pearsall, Texas, and then another facility in Conroe, Texas.

His wife and children were released from detention and allowed to reunite with Muhammad’s brother-in-law, who was acting as the family’s sponsor, in Utah.

Muhammad’s lawyers said Ice informed them that the agency had deemed him a “national security risk”, and that the agency did not need to provide any further details about why he had been separated from his family. The agency also repeatedly restricted him from speaking with lawyers, without explaining why.

Former officials and attorneys told the Guardian that Ice is increasingly using national security concerns as a catchall excuse for not providing clear information about why certain individuals are being detained, or denied access to their families and legal counsel.

As the weeks wore on, Muhammad consented to be deported to Brazil. He was hesitant – shaken by the episode when his daughter was kidnapped – but it felt like a safer choice than Afghanistan. But Brazil wouldn’t accept him.

So he kept asking to speak to his lawyers, and kept asking to apply for asylum in the US.

“I feel like I am alone and nothing of my future is within my control,” he said, after two months of detention.

His lawyers, meanwhile, were scrambling to schedule a meeting with him. They submitted multiple Freedom of Information Act requests to multiple immigration agencies, seeking to review Muhammad’s case files. Ice maintained that because it had deemed Muhammad a security risk, it did not have to comply with a court-ordered policy to make sure that parents and children who are separated by Ice are allowed regular calls and visits.

Finally, after nearly five months in detention, Ice referred Muhammad to the US Immigration and Customs Agency (USCIS) for an interview to determine his eligibility for asylum. Muhammed said officials there told him they were doing so in order to “cover their asses” – so they could check off the box and finally deport him back to Afghanistan.

“I miss the days that I would take [my children] out for ice-cream and walk through the park,” he said. “I also miss playing with them before bedtime to make sure that they would sleep well.”

Prolonged separations, including those lasting longer than five or six months, could cause a child welfare crisis, experts said.

In the aftermath of the family separation crisis during the first Trump administration, pediatricians, psychiatrists and other experts decried the deep psychological scars that the policy would leave on children.

A 2021 study found that the impacts of the separations persisted for weeks or months after families were reunited. “The longer the separation lasts, the more harmful it can be,” said Brané, the former DHS official, who led a taskforce charged with finding and reuniting separated migrant families and is now the executive director of the advocacy group Together and Free.

During 2018’s period of zero tolerance for migrant families, images of bawling children being ripped away from their parents at the southern border and forced into overcrowded makeshift shelters quickly began to raise public outrage and alarm. But now, Brané said, few asylum seekers are appearing at the southern border – and most of the separations seem to be occurring out of public view.

“But the intent is the same, and the impact is the same,” she said. “And I don’t know that they’re tracking this any better than they were before.”

Years after Trump ended the zero-tolerance policy, hundreds of children remained separated from their parents – though advocacy groups said it is impossible to know exactly how many, due to a lack of government records or tracking.

In some cases, parents were deported while their children remained in foster care. In other cases, when very young children were taken from their parents and spent years in foster care, parents have made the difficult decision to allow their children to remain in the US without them, rather than risk relocating and re-traumatizing them.

Amid a new wave of separations this year, attorneys have said the government in several cases has not complied with a 2019 court settlement – known as the “Ms L Settlement” – designed to prevent a second family separation crisis.

“It appears that families are not always receiving the notifications that they’re supposed to receive,” Brané said. “The government hasn’t been following certain norms and procedures.”

In the three cases reviewed in detail by the Guardian, parents had no idea where their children were being taken. Often, the parents didn’t know where they were themselves, either, and said that they were frequently denied access to calls with their lawyers. According to attorneys at Raíces and other legal aid groups, this has also been the case for other clients.

“The reality is that these are scenarios where there are no grounds for [separation], you know, based upon that settlement agreement,” said Al-Juburi. “And it’s much harder to keep families together when they are separated like this and for such extensive periods of time.”

Even after separating families, Al-Juburi noted, Ice has been moving parents around from one detention center to another, without advance notice to their lawyers or other family members – setting attorneys on a “wild goose chase” to find out where their clients have been moved.

After LW was separated from her child and moved from a detention center in Texas to another in New Jersey, attorneys at Raíces had to wait three weeks to schedule a phone call to consult on her case. On the day of her scheduled call, she was moved again without explanation or notice to El Paso, Texas, into the custody of CBP, and then two days later back to Ice custody in New Mexico.

Ice has told people in its custody, including LW, that they will be reunited with their children if and when they accept deportation, Al-Juburi noted. “But that should be taken with a grain of salt.” As the government increasingly moves immigrants around the country, often in chaotic and irregular ways, there’s a risk that families will be lost in the shuffle.

For some parents, the separations – and the subsequent confusion – were too much to bear. SP and her husband agreed to sign deportation papers after more than two months apart from their son.

The family had fled Mongolia in April this year, their lawyers said. After SP and her husband had attempted to expose public corruption and money-laundering allegations, they said their 11-year-old son was sexually harassed and physically abused at school – under the watch of administrators the parents believed were allied with Mongolia’s government.

The family arrived in Chicago on tourist visas, and were stopped straight away by immigration agents. Almost immediately, they were sent to an Ice facility for families in Texas – where they each struggled with the mental and physical toll of detention.

At one point, SP’s husband attempted suicide. At another, her son developed a persistent rash. Neither received sufficient care, her lawyers said.

A month later, Ice flew the family to New York – from where they were meant to be deported to Mongolia. But SP and her husband resisted – saying they would be in danger if they returned.

That’s when the government threatened to take their son away, according to a sworn declaration from SP in the family’s immigration case. A week later, it did just that. The family was called into a meeting, and they said no Mongolian interpreter was provided – so the 11-year-old was forced to translate for his parents.

“My child told me that Ice officers informed him they were going to take him ‘to a place in San Antonio’,” said SP in a sworn declaration in the family’s immigration case. “Neither my husband nor I understood why our child was being taken from us.”

The officers had whisked him away without explaining why or where he was being sent. They had left behind his inhaler. SP and her husband were shackled at their hands and feet and taken to another detention center, and separated from each other – again, without explanation – and only allowed to see each other once every three weeks.

“I am devastated by this situation,” SP told her lawyers a few days later. “I still do not understand … Ice officers have not explained anything to me.”

Her son turned 12 while he was staying with a foster family. Ice ignored repeated notifications by SP’s lawyers that the agency was violating a court settlement regarding family separations.

In the end, the agency said it would deport each family member back separately – and SP’s lawyers fought to ensure that, at least, the family could board the same plane out of the country.

Her lawyers have not been able to confirm that the family is still safe, back in Mongolia.

The Guardian has used first names or initials, rather than full names, in this article to protect people in Ice or CBP custody or who have been deported back to their countries of origin.

Contributors

Additional reporting: Will Craft

Illustrations: Angelica Alzona

Photo research: Gail Fletcher

Copy editor: Matthew Grace

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  3 weeks ago

3 weeks ago

Comments