NEW ORLEANS (AP) — A Tulane University researcher resigned Wednesday, citing censorship from university leaders who had warned that her advocacy and research exposing the Louisiana petrochemical industry's health impacts and racial disparities in hiring had triggered blowback from donors and elected officials.

In her resignation letter, Kimberly Terrell accused the university of sacrificing academic freedom to appease Louisiana's Republican Gov. Jeff Landry. Terrell, the director of community engagement at Tulane's Environmental Law Clinic claimed the facility had been “placed under a complete gag order” that barred her from making public statements about her research.

A spokesperson for Landry said this was “not accurate” but declined to comment further.

According to emails obtained by The Associated Press, university leaders wrote that the work of the law clinic had become an “impediment” to a Tulane redevelopment project reliant on support from state and private funders. The clinic represents communities fighting the petrochemical industry in court.

“I cannot remain silent as this university sacrifices academic integrity for political appeasement and pet projects,” Terrell wrote. “Our work is too important, and the stakes are too high, to sit back and watch special interests replace scholarship with censorship.”

Terrell said she resigned “to protect the work and interests” of the clinic.

Tulane spokesperson Michael Strecker said in an emailed statement that the university “is fully committed to academic freedom and the strong pedagogical value of law clinics.” He declined to comment on “personnel matters.”

Elected officials concerned about environmental law clinic's work

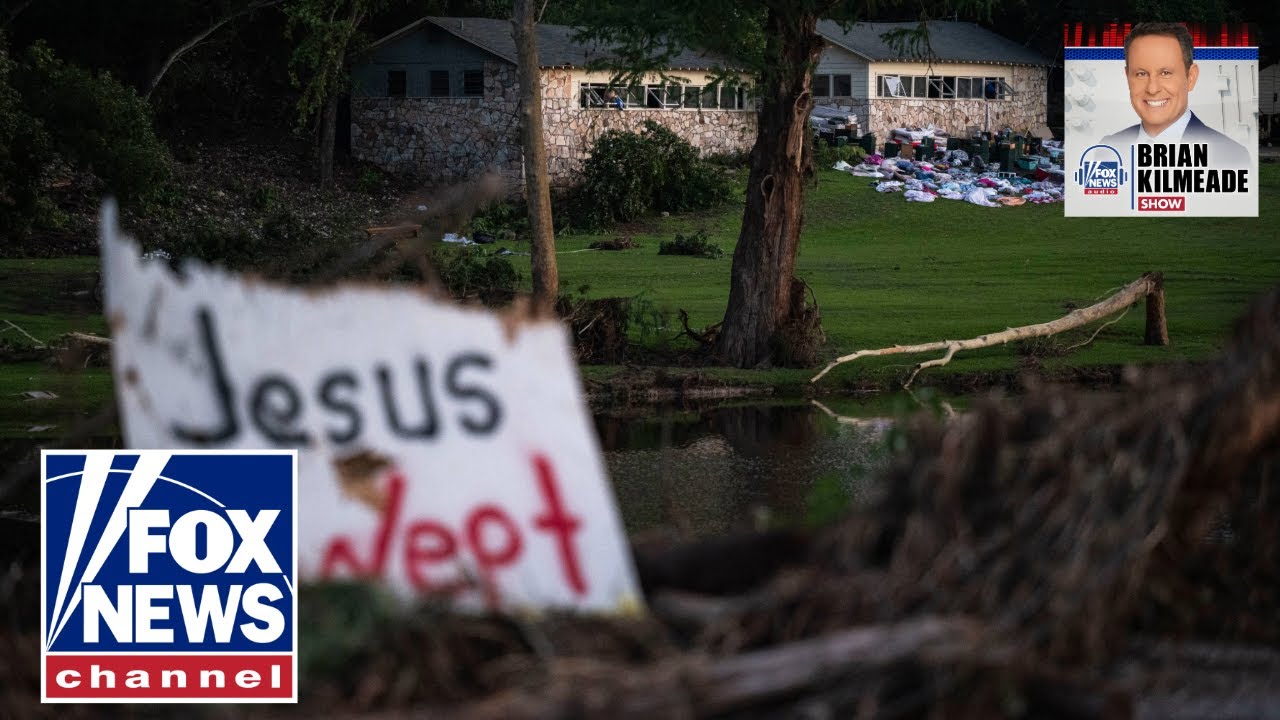

Many of the clinic's clients are located along the heavily industrialized 85-mile (137-kilometer) stretch of the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge commonly referred to by environmental groups as “Cancer Alley.”

In a May 4 email to clinic staff, Marcilynn Burke, dean of Tulane's law school, wrote that Tulane University President Michael Fitts worried the clinic's work threatened to tank support for the university's long-sought downtown expansion.

“Elected officials and major donors have cited the clinic as an impediment to them lending their support,” Burke wrote.

Burke did not respond to an emailed request for comment Wednesday.

In her resignation letter, Terrell wrote that she had been told the governor “threatened to veto” any state funding for the expansion project unless Tulane's president “did something” about the clinic.

Barred from media interviews

A 2022 study Terrell co-authored found higher cancer rates in Black or impoverished communities in Louisiana. Another study she published last year linked toxic air pollution in Louisiana with premature births and lower weight in newborns.

In April, Terrell published research showing that Black people received significantly less jobs in the petrochemical industry than white people in Louisiana despite having similar levels of training and education.

Media coverage of the April study coincided with a visit by Tulane leaders to Louisiana's capitol to lobby elected officials in support of university projects. Shortly after, Burke, the law school's dean, told clinic staff in an email that “all external communications” such as social media posts and media interviews “must be pre-approved by me.”

Emails from May show that Burke denied requests from Terrell to make comments in response to various media requests, correspondence and speaking engagements, saying they were not “essential functions of the job.”

On May 12, Terrell filed a complaint with the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges, claiming that her academic freedom had been violated. The agency, which accredits Tulane, did not immediately provide comment.

University leaders concerned about clinic's advocacy

In a May 21 audio recording obtained by the AP, Provost Robin Forman said that when Tulane leadership met with elected officials in April, they were pressed as to why ”‘Tulane has taken a stand on the chemical industry as harming communities’,” and this “left people feeling embarrassed and uncomfortable.”

Burke said in an email that university leaders had misgivings about a press release in which a community activist represented by Terrell's clinic is quoted as saying that petrochemical companies “prioritize profit over people.” Burke noted that Fitts was concerned about the clinic's science-based advocacy program, and Terrell's work in particular which he worried had veered “into lobbying.” Burke said Fitts required an explanation of “how the study about racial disparities relates directly to client representation."

The clinic cites the study in a legal filing opposing a proposed chemical plant beside a predominantly Black neighborhood, arguing the community would be burdened with a disproportionate amount of pollution and less than a fair share of the jobs.

The clinic's annual report highlighted its representation of a group of residents in a historic Black community who halted a massive grain terminal that would have been built around 300 feet from their homes.

The provost viewed the clinic’s annual report “as bragging that the clinic has shut down development,” Burke said in an email.

In her resignation letter, Terrell warned colleagues that she felt Tulane's leaders “have chosen to abandon the principles of knowledge, education, and the greater good in pursuit of their own narrow agenda.”

___

Brook is a corps member for The Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)

Comments