In 1971, the president of Mississippi State University, Dr. William L. Giles, invited President Richard Nixon to attend the dedication of U.S. Sen. John C. Stennis’ papers to the university library’s archives.

Nixon declined, but the Republican president sent a generous note in support of the veteran Democrat Stennis.

“Future students and scholars who study there will … familiarize themselves with the outstanding record of a U.S. Senator whose … judgment in complex areas of national security have been a source of strength and comfort to those who have led this Nation and to all who are concerned in preserving the freedom we cherish.”

Nixon’s prediction came true, perhaps ironically, considering the legal troubles over his own papers during the Watergate crisis. Congress passed the Presidential Records Act of 1978 after Nixon resigned.

Stennis’ gift to his alma mater caused a windfall of subsequent congressional donations to what is now the Mississippi Political Collections at Mississippi State University Libraries.

Now, 55 years later, Mississippi State University holds a body of records from a bipartisan group of officials that has positioned it to tell a major part of the state’s story in national and global politics. That story is told to over 100 patrons and dozens of college and K-12 classes each year.

The papers are fertile ground for scholarly research into Congress’ role in shaping U.S. history, with its extraordinary powers over lawmaking, the economy and one of the world’s largest militaries.

Mississippi State University, where I work as an assistant professor and director of the Mississippi Political Collections, is not alone in providing such a rich source of history. It is part of a national network of universities that hold and steward congressional papers.

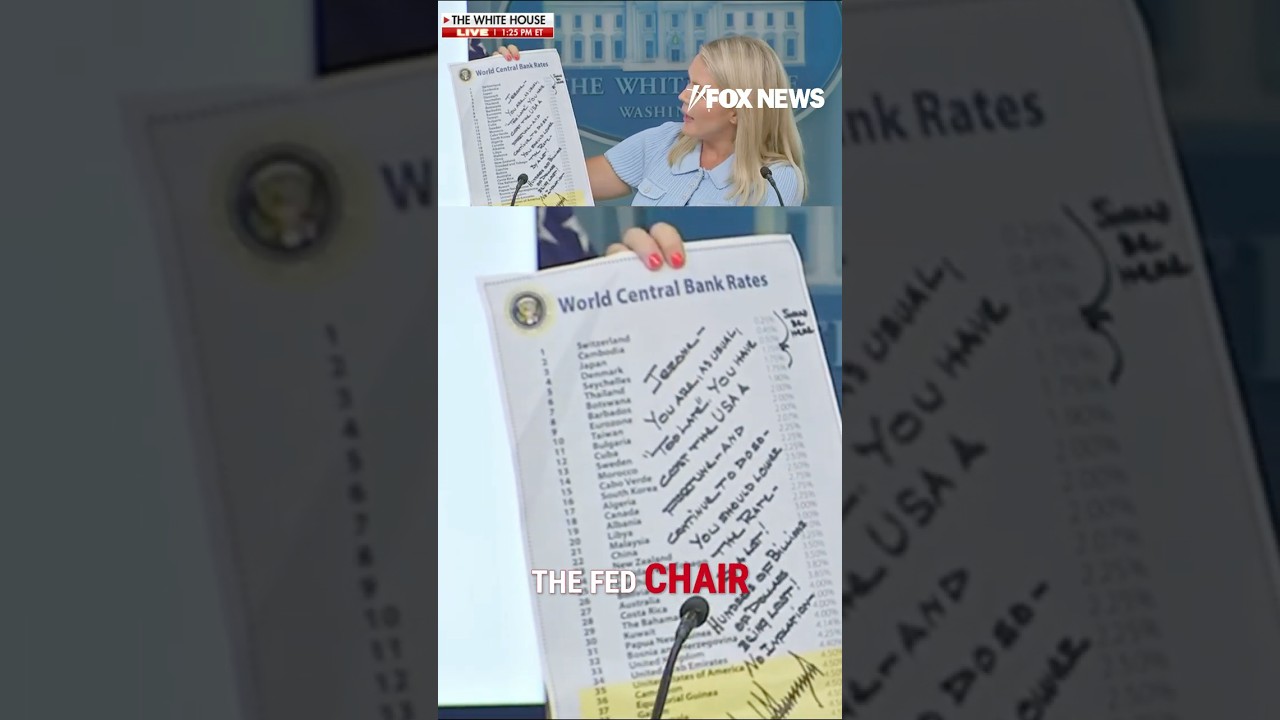

But support for this stewardship is in jeopardy. With the White House’s proposed elimination of independent granting agencies such as the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Institute of Museum and Library Services, it is unclear what money will be available for this work in the future.

From research to public service

Mississippi State University’s building of an expansive political archive is neither unique nor a break from practices by our national peers:

• The Richard Russell Library for Political Research and Studies at the University of Georgia – named after the U.S. senator from Georgia from 1933 to 1971 – has grown since its founding in 1974 into one of America’s premier research libraries of political history, with more than 600 manuscript collections and an extensive oral history collection.

• Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin donated his papers to Drake University to form The Harkin Institute, which memorializes Harkin’s role as chief sponsor of the Americans with Disabilities Act through disability policy research and education.

• Sens. Robert and Elizabeth Dole’s papers are the bedrock of the Dole Institute of Politics at Kansas University.

• In 2023, retiring Sens. Richard Shelby and Patrick Leahy donated their archives – Shelby to the University of Alabama and Leahy to the University of Vermont.

By lending their papers and relative political celebrity, members of Congress have laid the groundwork for repositories like these to promote policy research to enable local and state governments to shape legislation on issues central to their states.

More complete history

When the repositories are at universities, they also provide educational programming that encourages public service for the next generations.

At Mississippi State University, the John C. Stennis Institute for Government and Community Development sponsors an organization that allows students to learn about government, voting, organizing and potential careers on Capitol Hill with trips to Washington, D.C.

Depositing congressional papers in states and districts, to be cared for by professional archivists and librarians, extends the life of the records and expands their utility.

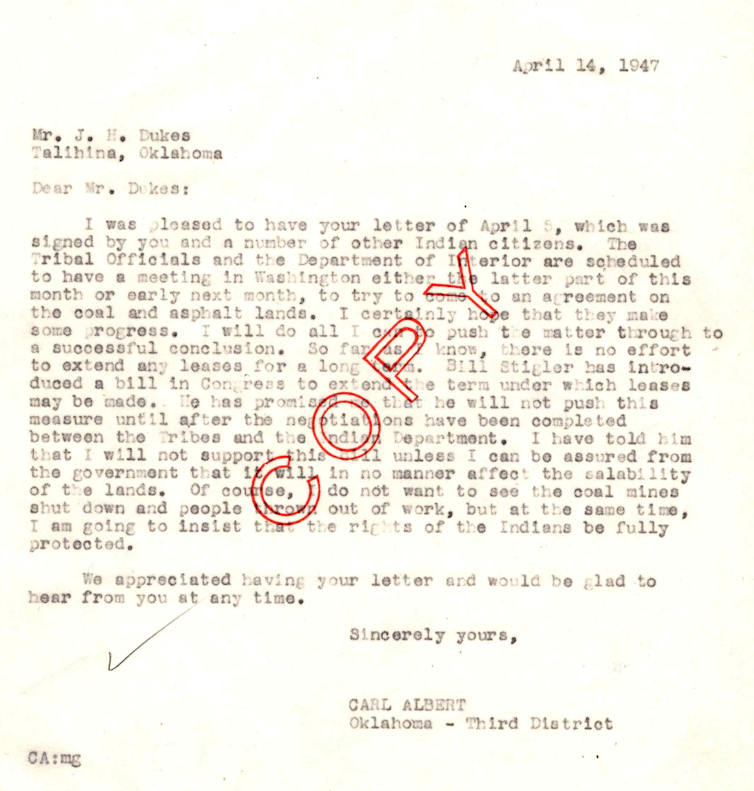

When elected officials give their papers to their constituents, they ensure the public can see and use the papers. This is a way of returning their history to them, while giving them the power to assemble a more complete, independent version of their political history. While members of Congress are not required by law to donate their papers, they passed a bipartisan concurrent resolution in 2008 encouraging the practice.

Users of congressional archives range from historians to college students, local investigative journalists, political memoirists and documentary filmmakers. In advance of the 2020 election, we contributed historical materials to CNN’s reporting on Joe Biden’s controversial relationship with the Southern bloc of segregationist senators in his early Senate years.

Preserving the archives

While the results contribute to the humanities, the process of archival preservation and management is as complex a science as any other.

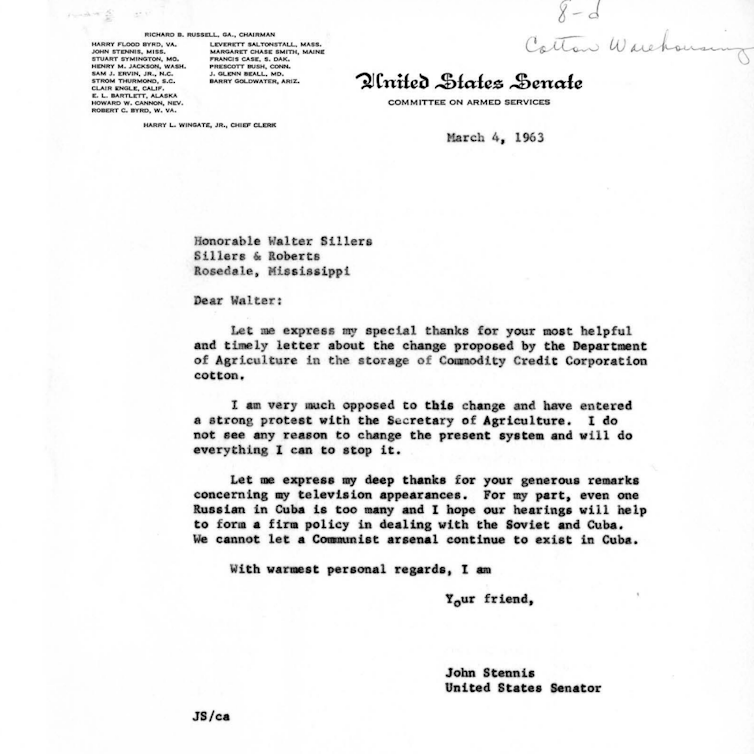

“Congressional records” is a broad term that encompasses many formats such as letters, diaries, notes, meeting minutes, speech transcripts, guestbooks and schedules.

They also include ephemera such as campaign bumper stickers, military medals and even ceremonial pieces of the original U.S. Capitol flooring. They contain rare photographs of everything from natural disaster damage to state dinners and legacy audiovisual materials such as 8 mm film, cassette tapes and vinyl records. Members of Congress also have donated their libraries of hundreds of books.

Archival preservation is a constantly evolving science. Only in the mid-20th century was the acid-free box developed to arrest the deterioration of paper records. After the advent of film-based photographs, archivists later learned to keep them away from light and heat, and they observed that audiovisual materials such as 8mm tape decompose from acid decay quickly if not stored in proper conditions.

Alongside preservation work comes the task of inventorying the records for public use. Archivists write finding aids – itemized, searchable catalogs of the records – and create metadata, which describes items in terms of size, creation date and location.

Future congressional papers will include born-digital content such as email and social media. This means traditional archiving will give way to digital preservation and data management. Federal law mandates that digital records have alt-text and transcription, and they need specialized expertise in file storage and data security because congressional papers often contain case files with sensitive personal data.

With congressional materials often clocking in at hundreds or thousands of linear feet, emerging artificial intelligence and automation technologies will usher this field into a new era, with AI speeding metadata and cataloging work to deliver usable records for researchers faster than ever.

No more funding?

All of this work takes money; most of it takes staff time. Institutions meet these needs through federal grants – the very grants at risk from the Trump administration’s proposed elimination of the agencies that administer them.

For example, West Virginia University has been awarded over $400,000 since 2021 from the National Endowment for the Humanities for the American Congress Digital Archives Portal project, a website that centralizes digitized congressional records at the university and a growing list of partners such as the University of Hawaii and the University of Oklahoma.

Past federal grants have funded other congressional papers projects, from basic supply needs such as folders to more complex repair of film and tape.

The Howard Baker Center for Public Policy at the University of Tennessee used National Endowment for the Humanities funds to purchase specialized supplies needed to store the papers of its namesake, the Republican senator who also served as chief of staff to President Ronald Reagan.

National Endowment for the Humanities funds helped process U.S. Rep. Pat Williams’ papers at the University of Montana, resulting in a searchable finding aid for the 87 boxes of records documenting the Montana Democrat’s 18 years in Congress. President Franklin D. Roosevelt said, “I have an unshaken conviction that democracy can never be undermined if we maintain our library resources and a national intelligence capable of utilizing them.”

With the current threat to federal grants – and agencies – that pay for the crucial work of stewarding these congressional papers, it appears that these records of democracy may no longer play their role in supporting that democracy.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  6 hours ago

6 hours ago

Comments