In early October, Tracy Wright invited a group of other women in her social circle – all fellow knitters – to gather outside the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facility in their home town of Portland, Oregon. They were “armed with their weapons of mass construction”.

Donald Trump had just ordered national guard troops deployed to the city, which he called “war ravaged” in order to protect ICE facilities he said were “under siege” by anti-fascists “and other domestic terrorists”.

Wright wanted to show that life was continuing on as normal in Portland, and be a friendly face greeting any immigrants arriving at the ICE facility for appointments. But “I didn’t want to go by myself,” she said. “I wasn’t sure what to expect.” So, she and the other women – who would eventually nickname themselves “Knitters Against Fascism” – brought their knitting needles and lawn chairs, and returned week after week.

Word of the “knit-ins” quickly spread by word of mouth and social media: when a friend at her local knitters guild mentioned the protest, knitwear designer Michele Lee Bernstein decided to attend to show that Portland wasn’t “burning to the ground”.

“A group of knitters calmly knitting was a perfect visual to counter the lie,” she said. Knowing other crafters would be there “made it easy to participate”.

At the second protest she attended, Bernstein designed a hat based on the Portland Frog, an inflatable costume that a brigade of protesters wore at similar protests outside the local ICE facility.

“Small acts can make big change,” said Bernstein. She posted the frog hat pattern on her website and a month later learned that a church group had raised $550 for a local food bank by selling hats they’d knit with the pattern. Bernstein also sold one of the hats she made herself for $100 and donated the funds to the North-east Emergency Food Program – at a time when need at nationwide food banks was high due to cuts to Snap benefits.

“Even if we’re not all down at ICE, we’re working together to do something good,” she said.

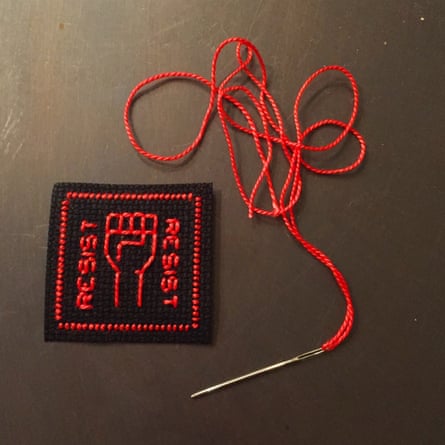

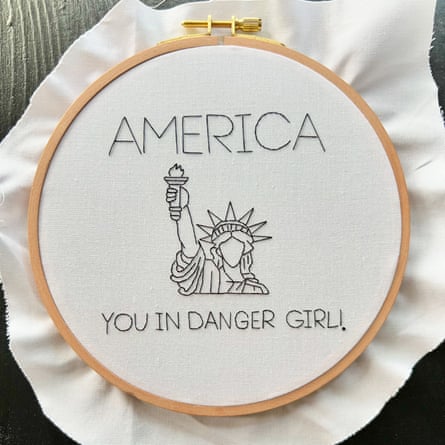

Wright and Bernstein are part of a centuries-long tradition of fiber artists who’ve worked toward political goals through their crafts. In 2003, writer Betsy Greer coined the term “craftivism” to describe that particular brand of activism – but knitters, crocheters, sewers, embroiderers and other makers have long used their art to speak out against environmental degradation, racism, wealth inequality, fast fashion and other social issues. From the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, who embroidered the white handkerchiefs they wore to protest against the disappearances of their children during Argentina’s military dictatorship, to the Aids Memorial Quilt, which wove together quilt blocks memorializing people lost to Aids, much of the success of those projects has been in the communities they’ve built.

“One of the big challenges in movement building is to build solidarity across different groups of people,” said Hahrie Han, a political scientist at Johns Hopkins University and 2025 MacArthur Fellow. “At a certain point in the history of every social movement that has ever changed the world, there’s a point at which the movement gets challenged, or things get hard for whatever reason. And in moments of stress, the motivations that keep people together or that keep movements together are often their social-relational commitments, more than their commitment to the issue.”

That is, people are more likely to continue protesting or attending town halls or knitting outside ICE facilities if they don’t want to let down their friends.

Shannon Downey discovered the power of craft as a movement building tool more than a decade ago, after a shooting occurred outside her home and a bullet went through her bedroom window. In the aftermath, she realized that even though she was thinking constantly about gun violence, she had no relationship with guns.

So she “sat down and stitched a gun” to have time to reflect on what the weapon looked like and what it might be like to hold.

An embroidery artist, Downey said her work was initially private and self-reflective. But she later shared it on Instagram and her followers started asking for a pattern so they could embroider their own. Eventually, 2,000 of those followers mailed Downey the guns they had embroidered. At a fundraiser for the Chicago-based non-profit Project Fire, which works with young victims and perpetrators of gun violence, Downey raised $5,000 by selling the embroidered works.

The success of that initial fundraiser inspired her to continue working at the intersection of craft and activism, and start hosting workshops along that theme. There, she realized how quickly strangers bonded around a shared craft.

“I just started to see this as, like, the greatest community organizing tool that could exist,” she said.

A common example is the “pussyhat”, which many protesters knitted to denounce Trump at the beginning of his first administration. “It was an identity and allegiance signaling tool,” said Downey, “which is one important and very small part of activism.”

For some people, knitting a pussyhat or embroidering a feminist statement is the boldest thing they’ve ever done or the most they’ve ever said publicly about their political beliefs, she said. Last year, Downey published Let’s Move the Needle: An Activism Handbook for Artists, Crafters, Creatives and Makers, a book to help readers think through the question: “What’s the next brave thing that I can do?”

For some, that might be joining a social circle around their craft or selling their work to raise funds for a cause. For others it might be picking an issue, targeting its root causes and choosing goals, tactics and a message to bring about a change.

“Community building alone is not enough to build a movement,” said Han, the political scientist. A movement must bring “people into community with each other so that they begin to understand the ways in which what they can do together is greater than what they can do alone” and also become a space through which they “realize their interests in the public sphere”.

When she hosts workshops, Downey said: “My job is to make sure that you have the best experience ever so that you want to come back again.” That community forms the foundation for whatever comes next.

She notes powerful craft communities that have come together without centering politics in their work, such as the Loose End Project, which pairs crafters with families that have lost a loved one to finish the sweaters, quilts, blankets and other projects their family member left behind.

“What’s incredible is the people that are completing pieces for people who have lost people” who might not get along outside the project, she said. They might not share the same politics or religion, “but they’re forgetting about all of that, suspending all of that, and connecting through their humanity through this object.”

Other craft communities have centered on a political or social aim. The non-profit Knit the Rainbow, for example, invites knitters to make warm clothing for LGBTQ+ youth in New York City’s foster system and homeless shelters. The Liberty Crochet Project, meanwhile, brought crocheters together in protest with a collaborative mural denouncing the supreme court’s decision to overturn Roe v Wade. And the mother-daughter-owned Danish yarn brand Knitting for Olive made headlines in August when it raised $828,868 in one weekend for Unicef’s work in Gaza.

“While we, as a knitting community, obviously can’t end a war, placing an order on the donation day gave people a way to take action,” said Caroline Larsen, who co-owns Knitting for Olive with her mother, Pernille. The company’s August fundraiser was their seventh since 2020, when they began fundraising for Black Lives Matter in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. “Supporting people in need matters more to us than having an impressive number on our bottom line. Our everyday lives don’t change because of that number, but these donations can make a real difference for someone who needs it far more than we do.”

For some fiber artists, craft is inherently political. “Creating in a time of destruction and chaos, that is resistance in and of itself,” said Downey, who adds that, for many, making their own clothing is a powerful rebuke of fast fashion.

But she thinks one of the other successes of craftivism is that “it centers joy”.

“There’s a lot of anger and rage in the work that I do, that’s the catalyst,” she said.” But you can’t live in that energy.” Creating communities around a shared passion, she believes, makes the work sustainable.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  3 weeks ago

3 weeks ago

Comments