When the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) altered its website last month to reflect US health secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr’s belief of a causal link between vaccines and autism – a claim that has been debunked by dozens of scientific studies – autism advocates sprang into action.

Leaders at the Association of University Centers on Disabilities demanded online that public health officials “listen to autistic voices”.

Advocates at the Autistic People of Color Fund called on supporters to donate to its mutual aid fund.

“Kennedy’s lies endanger public health and the disabled community,” the Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN) wrote in bold letters in an infographic on Instagram.

“On all of our platforms, we immediately directed our community to alternative sources of public health information, sources that aren’t under attack by conspiracy thinking or anti-science approaches,” said Zoe Gross, the director of advocacy at the ASAN, the largest US nonprofit operated entirely by autistic people.

Advocates said combating autism misinformation has become a game of Whac-A-Mole since Kennedy, a longtime anti-vaccination leader, was appointed to head the Department of Health and Human Services in February. While they’ve been building an autism awareness and acceptance movement for decades, advocates are shifting focus to combat rhetoric that could set progress back. They’re speaking out more than ever before, with groups joining together to launch months-long communications campaigns to keep families confident in science.

“Our community looks to us to give them the facts,” said Maria Davis-Pierre, an autistic licensed mental health therapist and the founder of Autism in Black, an organization that calls attention to racial disparities in autism diagnosis and care. “We have to constantly refute RFK’s information since we know that misinformation will harm our community more than any other community out there.”

Fighting misinformation is at the movement’s core

Though autism spectrum disorder was first identified in the 1940s, advocates still spend an outsized amount of time educating the public about what autism is and isn’t – a role that’s only grown more challenging in recent months.

Autism is a developmental condition that affects how someone communicates and behaves, encompassing those who can live independently and others who need support due to severe symptoms such as language and functional impairments. In the 1980s, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) identified diagnostic criteria for autism, but the movement for autism recognition faced a major hurdle in the 1990s, when a medical paper implied a link between the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine and autism. The study, which looked at 12 children who received the vaccine – eight of whom were said to develop autism – was retracted in 2010 for insufficient evidence, among other problems. Since then, large epidemiological studies on various vaccines have found no relationship between vaccines and autism.

Yet the idea that vaccines cause autism persists, with Kennedy breathing new life into it.

“When [Kennedy] says something appalling, we get a week or two where all I can do is answer press inquiries because that’s how many we’re getting. It becomes my whole job,” Gross said. “It’s disappointing to have to fight the same stuff we were fighting when I came into autism advocacy 15 years ago.”

The ASAN has released dozens of statements over the past few months in response to the administration, with materials in plain language and picture-assisted format to reach people with varying accessibility needs. The Autism Science Foundation, which funds research about autism’s causes and treatments, has even partnered with the American Academy of Pediatrics to design infographics and tools to illustrate to families that vaccines do not cause autism. “We’re having to go backwards and reassure parents,” said Alycia Halladay, the organization’s chief science officer.

Since Kennedy was confirmed, the administration has repeatedly framed autism as a chronic disease that needs to be “investigated”, though autism is a neurological and developmental disorder and not something to be cured, advocates and researchers say.

In April, when the CDC released its biennial report about autism prevalence in children, Kennedy called the rise in children with autism – from 1 in 36 in 2020 to 1 in 31 in 2022 and from 1 in 150 in 2000 – “alarming” and a sign that “the epidemic is real”. Though the CDC report stated that the rise is a result of better autism screening, wider diagnosis parameters and greater access to services, Kennedy refuted the findings, saying the increase was due to “environmental toxins”.

Advocates again doubled down on storytelling and education to counter Kennedy’s claims.

For example, leaders at Autism Empowerment not only shared evidence-based information on social media, but also helped autistic adults share their stories through the autistic-led publication Spectrum Life Magazine, community outreach events and other programs.

Then, when Kennedy pledged to create a national autism database to find the causes of autism, advocates pushed back with a Change.org petition that garnered nearly 50,000 signatures. Opponents explained that Kennedy’s vague plan for a registry could turn into a means for the government to track autistic people and restrict their ability to participate in society. Three days later, Kennedy reversed course. Advocates believe the public outcry influenced his decision.

“To speak as though our existence is some kind of calamity that must be eliminated is a form of eugenics – the dangerous ideology based on the idea that ‘some people are born to be a burden on the rest,’” the ASAN wrote in a statement. “Such ideas led directly to disabled people being incarcerated and forcibly sterilized in this country, and murdered in Nazi Germany, and it is profoundly disturbing to see this administration bringing back yet another hallmark of authoritarian policy.”

In September, when Trump and Kennedy claimed that taking acetaminophen during pregnancy leads to autism, Davis-Pierre was quick to share local resources that would actually help families. Davis-Pierre is familiar with being misled and shut out when trying to navigate support networks – she was diagnosed later in life and led a weeklong sit-in at the pediatric neurologist’s office to get her child’s autism diagnosis.

“The fear-mongering will lead to gaps in diagnosis that we have been trying to bridge when it comes to the Black community. People are scared now,” said Davis-Pierre. “While I would love for this administration to take accountability, I think we’re just going to have to buckle in for the rest of this term and understand that our community must work hard to refute this misinformation.”

Autistic people need more resources – so advocates are leaning into politics

Significant challenges remain in improving quality of life for autistic people. Autistic children and adults face limited access to health and wellness assistance, long waitlists for diagnosis and services, and shorter life expectancy. They also face barriers to employment, housing, and food security.

To address these issues, advocates want to shift the government’s focus away from pouring money into disproven theories and toward tangible efforts that help autistic people in real time.

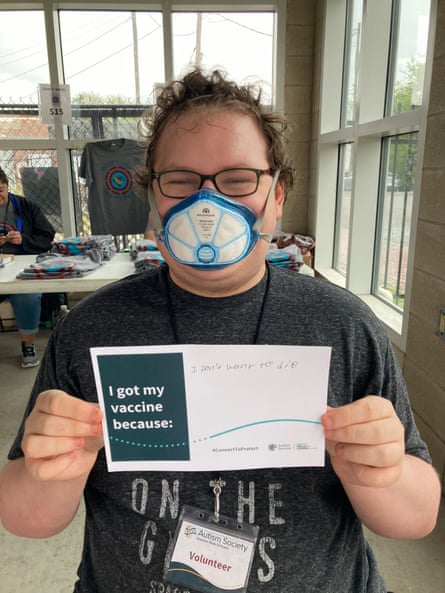

The Autism Society of Greater New Orleans has seen success with boosting vaccine confidence and access among autistic people through a multi-pronged approach. During the program’s peak in 2023, the organization vaccinated 2,029 people, exceeding their goal of 600. They also trained 300 medical professionals on how to better administer vaccines and make sensory environments more comfortable for people with autism, since many practitioners in the area did not have specialized knowledge. The organization has also developed and distributed more than 1,000 vaccine kits for autistic people, which included headphones, sunglasses, fidgets, and shock blockers, to help reduce the pain of getting a shot.

“People told us that the kits completely changed their experiences with vaccines,” said Claire Tibbetts, the chapter’s executive director. “Children and adults with autism had less fear and anxiety around the physical experience of getting vaccines.”

The organization, like many autism advocacy groups, has also turned to advocating for better-funded services, early intervention and early diagnosis. In the Greater New Orleans area, patients on Medicaid must wait two years for an autism diagnosis, since there are few providers who take Medicaid and offer the test, Tibbetts said. One national study found the average wait time to schedule an appointment to be about three months, a figure advocates and medical professionals say is too long. Without a diagnosis, autistic people can’t access developmental disability services, including in-home professional support, child care or respite care.

Advocates also plan to put more pressure on elected officials, with some organizations calling for Kennedy’s removal.

During Trump’s first term and Biden’s presidency, advocates regularly communicated with the health department, but a sudden communications freeze in January, as Trump appointees laid off thousands of staffers at the agency, meant they no longer had a seat at the table.

“We have requested meetings with HHS staff and hope we can get those meetings so that we can engage directly with people both at the NIH and CDC about the vaccine question and other questions pertaining to responsible autism research,” said Jill Escher, the president of the National Council on Severe Autism.

Other advocates have made their way to Capitol Hill. Tonya Haynes, an advocate with Autism Speaks, accompanies her 25-year-old autistic son, Tyler, to deliver speeches about his experience graduating from college and being employed with autism.

“It’s one thing to read about Tyler’s story or to be told about Tyler’s story, but when individuals are able to see Tyler in person, the impact is instant,” said Haynes.

When the Senate voted to confirm Kennedy as health secretary, Louisiana Republican senator Bill Cassidy cast the deciding vote, though he expressed major concern over Kennedy’s anti-vaccination activism. To reassure Cassidy, Kennedy made several concessions – including leaving intact the CDC webpage that states vaccines do not cause autism. Now that Kennedy has breached that promise, Cassidy has expressed shock but has refused to directly challenge Kennedy.

As one of Cassidy’s constituents, Tibbetts said she and her team repeatedly meet with Cassidy’s office to share information about vaccines and autism – something they will continue to do as long as misinformation is spread. “Framing autism as some kind of disease that needs to be eradicated is harmful,” she said. “It hurts autistic people living their lives right now.”

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  3 weeks ago

3 weeks ago

Comments