President Donald Trump is making full use of his pardon power. This year, Trump has issued roughly 1,800 pardons, or nearly six times the number he issued during the four years of his first term. Granted, about 1,500 of them involved individuals charged for their role in the Jan. 6, 2021, assault on Congress. Still, the pace of Trump’s pardons this year have been nearly unprecedented.

That is, until you remember his predecessor. Joe Biden, at the end of his term, issued a full and sweeping pardon to his son Hunter for gun and drug charges. This was an unprecedented action by a president to pardon his own child, which had never been done before. Biden also granted pardons to several other family members on his final day in office.

Despite serving a single term, Biden holds the record for the most acts of clemency, or pardons combined with commuted sentences, of any president. It’s a record that’s not hard to imagine Trump could break.

As a political scientist who has studied pardons and other aspects of presidential power, I believe that the founders of our nation would be horrified by the contemporary use of the pardon power, which represents a far cry from the unifying act of mercy it was intended to be. While Biden issued pardons to family members, Trump has handed them out to political allies.

It remains to be seen whether this is a slight deviation from course or becomes a permanent pattern for all presidents in the future.

A clear break

There’s no question that Trump and Biden have acted within their authority in issuing pardons for federal offenses. Presidents can extend a pardon, or complete legal forgiveness of a crime, or a commutation, which is the reduction of a sentence. However, individuals pardoned for federal crimes may still face peril in state courts.

This extraordinary power may seem kinglike at first glance, but it was given to the president with a different vision in mind. The founders of the country viewed the pardon power not as a personal token for the president to hand out but as an act of mercy meant to check the other two branches.

If Congress passed a law that the president believed was poorly written, or if the courts unfairly punished someone for breaking it, the president could step in and right the wrong. This was seen by the founders as a merciful act, stemming from the tradition of old English law.

Throughout American history, we have seen presidents mostly adhere to this pattern. Both Abraham Lincoln and his successor Andrew Johnson issued pardons and amnesty to former Confederate citizens, with the aim of helping the nation come back together after secession and the Civil War. Harry Truman granted amnesty to certain World War II deserters, while Jimmy Carter granted pardons to hundreds of thousands of individuals who dodged the draft during the Vietnam War.

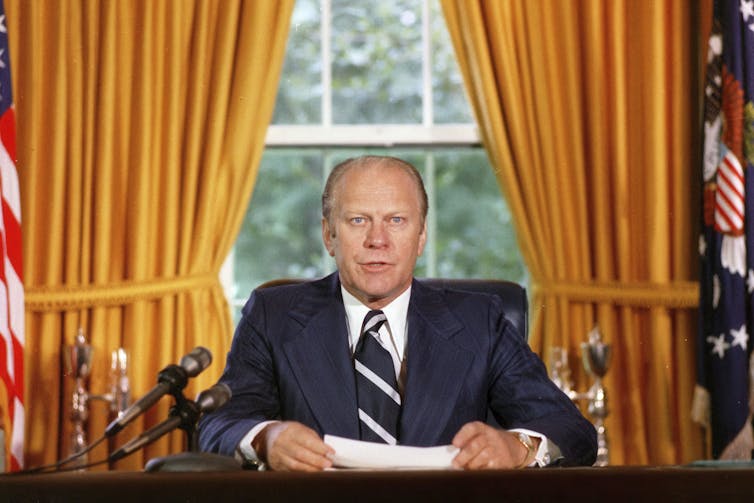

But toward the end of the 20th century and into the 21st, presidents have used the pardon pen increasingly for personal and political reasons. The inflection point is undoubtedly the pardon of former President Richard M. Nixon in 1974 by his former vice president and successor, Gerald Ford. This was issued a month after Nixon’s resignation in the wake of the Watergate scandal, which involved Nixon’s 1972 reelection campaign spying on his political enemies.

Ford justified his action by citing the need for national unity, saying the pardon would spare the country from a messy and dramatic public trial of a former president. Never before had a high-profile public politician received such a presidential grant, which caused Ford’s public standing to take a hit. Scholars and historians believe the act contributed to his reelection loss in 1976.

We have since seen Ford’s decision open the door to more pardons of political allies or personal friends. In 1992, George H.W. Bush pardoned officials he had served with in the Reagan administration who were tangled up in the arms-for-hostages, Iran-Contra scandal; Bill Clinton pardoned Democratic donor Marc Rich in 2001; and George W. Bush commuted the sentence of vice presidential aide Scooter Libby in 2007.

Trump’s expanded use

As it happens, Trump issued a full pardon to Libby in 2018. During his first term, Trump also pardoned Charles Kushner, the father of his son-in-law, Jared Kushner.

At the end of his first term, Trump pardoned “”) his former campaign manager Paul Manafort and his friend Roger Stone among other political allies.

Trump’s second term has seen clemency for his former lawyer and friend Rudy Giuliani, as well as crypto executive Changpeng Zhao, whose ties to Trump family businesses have raised questions about the pardon.

Trump’s use of the pardon power does not seem to follow a consistent doctrine or philosophy. Some of his clemency actions seem to contradict his administration’s policy, such as dozens of pardons of drug traffickers, despite the effort to stop drug trafficking in the Caribbean.

The pace of Trump’s pardons and commutations, however, suggests little hesitation. The question looking forward, beyond his presidency, is how much of a precedent his actions, along with Biden’s, may set for their successors.

We know this from earlier expansions of the pardon’s reach, as well as other areas of presidential authority: Few presidents willingly relinquish powers accrued by their predecessors. Once chief executives have exercised a certain type of authority, their predecessors seldom give it back, ultimately increasing the power of the presidency.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  2 weeks ago

2 weeks ago

Comments